Too often great ideas are kept in-house without recognizing their potential to create change beyond the communities where they are born. COA’s Innovative Practices Award (IPA) identifies, documents, and celebrates examples of successful approaches to management and service delivery practices adopted by our accredited organizations.

In 2020, a committee made up of COA volunteers and staff selected 4 finalists to move forward with a full case study. Alternative Family Services (AFS) came out the winner. Read on to find out how the AFS Enhanced Visitation Model kept families in touch during the crisis of COVID-19.

Helping families stabilize, heal, and reunify is an essential part of the work at Alternative Family Services. In-person visitation between kids in foster care and their biological family members is an integral part of the therapeutic process. The frequency of visits between parents and their kids are one of the strongest predictors of the family reuniting. The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated the challenges kids and families must overcome on their journey towards reunification.

As the magnitude of the COVID-19 pandemic became more apparent, AFS staff and clients were suddenly faced with the reality that in-person visitation between kids and their family may be halted, or at the very least severely restricted. The ever-changing state and county guidelines added uncertainty and stress to the situation. Since many of our AFS staff, biological families, and foster families are considered a “higher-risk” demographic to have serious consequences from COVID-19, there was palpable fear in conducting in-person visits. AFS staff knew it was critical for families to continue to stay connected, especially during such uncertain times. So, a taskforce was formed that included representation from key AFS stakeholders. The group was asked to create a safe and equitable plan that would allow in-person visitation to resume. After much input and deliberation, the Enhanced Visitation Model was approved.

Exploring the AFS Enhanced Visitation Model

Health Risk Assessment

It was important for AFS staff to evaluate and address client’s COVID-19 concerns and mitigate the risk of individual exposure to the virus. The taskforce sought input from its constituents, researched professional resources, and ultimately developed the “Wellness Questionnaire.” Staff can rapidly administer this assessment tool to determine COVID-19 risk factors each visitor had been exposed to within the 14 days prior to an in-person visit.

Visitation Service Plan

A “Visitation Service Plan” is a simple, flexible, and predominately check-box/circle-based tool that seamlessly incorporates the risk factors identified in the “Wellness Questionnaire,” assigning families to one of three visitation service levels according to COVID risk level:

- Community-based (Low Risk): local government, community mandated precautions only (masks, handwashing, appropriate hygiene precautions)

- Social Distance Enhanced (Moderate Risk): physical distanced “Enhanced Visitation Venues” required

- Virtual Visitation (High Risk): virtual visitation only

AFS staff wanted to provide therapeutic strategies in a fun, genuine, and safe environment regardless of their Visitation Service Plan. Once the assessment and planning tools were established, staff needed to create pandemic-safe stations for families to interact.

Enhanced Visitation Venues

When families have a positive, stress-free visit, they are more likely to retain and practice the therapeutic skills they learn. So, AFS staff developed a variety of indoor and outdoor “Visitation Venues” that are fun, affordable, replicable, and portable. The visitation venues meet COVID-19 safety protocols so parents and their children can safely interact. Here are some examples of our indoor and outdoor venues:

Indoor Visitation Venues

- The Hugging Station provides families with the opportunity to physically embrace, parents and children put on arm-length disposable gloves before reaching through sleeves attached to a transparent plastic curtain so they can safely hug during the pandemic. The Hugging Station can be easily decontaminated after each use.

- Activity Tables feature a Plexiglas divider, which sits on a table with parents on one side and child(ren) on the other. Participants can paint outlines of each other, play Tic-Tac-Toe or jointly create drawings with dry-erase markers, among other options.

- The Interactive Puppet Theater is where kids and parents make easy-to-construct sock puppets to safely “perform” in the puppet theater. It was designed with a table, clamps and Plexiglas with precut holes modified with rubber shields. AFS organized one-hour sock puppet workshops for staff so they can teach clients how to construct their own puppets for this playful encounter.

- Gaming Stations featuring video game consoles and large television screens allow families to play video games together while sitting at least six feet apart from one another, to ensure proper social distancing.

Curious to see what these options look like? Check out this video that highlights our indoor visitation venues.

Outdoor Visitation Venues

Since research has shown COVID-19 is less likely to spread between individuals while outdoors, AFS staff has developed a variety of safe outdoor venues that can easily be setup and disinfected after each use. When visits occur in the parking lots of one of our offices, artificial turf and gymnastic mats provide ground cover for families to play outdoor games. Pop-up tents provide shade when necessary, and bikes and tricycles are provided for families to ride together (staff uses a Clorox Total 360® Disinfectant Cleaner between uses).

AFS Visitation in 2021

The AFS Enhanced Visitation Model, funded with the assistance of the Walter S. Johnson Foundation, was the winner of COA’s 2020 Innovative Practices Award. While we were humbled to be selected, we are always striving to be innovative when it comes to providing the highest level of care to our children and families. At the end of every Enhanced Visitation Session, staff collects feedback from families to see what they like and what they feel has room for improvement.

While we are thankful that the COVID-19 vaccine is being distributed, AFS will continue to adhere to our Enhanced Visitation Model for the foreseeable future to ensure that staff, families and resource parents remain safe.

The views, information and opinions expressed herein are those of the author; they do not necessarily reflect those of the Council on Accreditation (COA). COA invites guest authors to contribute to the COA blog due to COA’s confidence in their knowledge on the subject matter and their expertise in their chosen field.

Alternative Family Services

Founded in 1978, Alternative Family Services (AFS) provides thoughtful, informed care, adoption and mental health services to foster children and youth throughout Northern California. The mission of Alternative Family Services is to support vulnerable children and families in need of stability, safety and wellbeing in their communities.

AFS, a COA-certified foster family agency, currently serves the diverse and varied needs of 1,500 foster youth, plus their biological and foster families, in the San Francisco Bay Area and Greater Sacramento Regions. Services provided by AFS include therapeutic foster care, Intensive Services Foster Care, support for foster children with developmental disabilities, therapeutic visitation, community-based mental health services, transitional housing support, independent life skills training, and much more.

A big thank you to Ruben Mina, LMSW for this guest post!

Can you tell me the history of your community?

Can you tell me some histories of your community?

Yes, histories.

Do you ever ask these questions of adolescents with whom you work? There is a distinction between the two questions. The first question focuses on one story: the prevailing story of how a community came to be what it is. It feels like asking adolescents to pull something in from the past, make sense of it and connect to it.

The second question asks adolescents to tell histories of their community. It invites them to share the who, what, how, and why about the people, institutions, political forces, cultures, and much more that make their community dynamic. Like adults, adolescents have a range of experiences in the communities to which they belong that are rooted in traditions they observe, inequities or injustices they endure or witness, and forms of oppression about which they are aware. They deserve the space to tell their stories. Each individual experiences and interprets life in their community in ways that cannot, and should not, be captured by a single history. By creating space for adolescents to share their varied perspectives and experiences, we are supporting their social and emotional development.

This is not about adolescents being unable to make sense of standard accounts of history. Nor is it about making up stories. It is about engaging adolescents in critical thinking and critical dialogue so that the histories they see, feel, and live each day are amplified. This deepens their connectedness to their respective communities, cultivates empathy, and provides a foundation for them to work collectively to transform their communities.

Mapping histories

While both questions at the beginning of this blog post could create opportunities for shared learning, focusing on multiple histories of a community does more. It invites adolescents to further develop self-efficacy by telling and showing one another the ways they view the world around them. Youth-serving programs want to build adolescents’ sense of self-efficacy, while letting them know that their voices matter. We let them know their voices matter when the learning that happens in human service organizations honors their perspectives.

Earlier in my career, I developed a group activity called “Community Stories” as a way to center adolescents’ experiences, while facilitating their exploration of ways they could transform their communities. This activity has helped adolescents in the Bronx in grade levels ranging from upper elementary school to high school identify and raise awareness about issues such as domestic violence and a lack of neighborhood parks that were impacting their daily lives.

Community Stories take the form of maps that reflect adolescents’ insights about experiences they have in a community to which they belong. It integrates numerous concepts and approaches, including: popular education concepts (participatory, group-oriented), photovoice, and community asset mapping, as well as literacy-building activities. The maps require basic art supplies and no art skills; they are animated by the dialogue adolescents engage in about the ways a group 1) experiences a shared community and 2) envisions its transformation.

This activity allows adolescents to explore a community they identify with in creative, empowering ways, and is intended to engage them in a communal exercise. Constructing maps to tell community stories allows adolescents to reimagine their communities and envision their transformation. By trusting and engaging the expert wisdom of adolescents’ lived experiences, you are letting them know that you value their agency.

Before creating maps, the group must identify a community to which they feel connected and would like to represent on a map. Since communities are not strictly defined by physical borders, it is vital to encourage consideration of non-geographic communities (i.e. community of teen activists). This is crucial for two reasons. First, adolescents are in the developmental stage of exploring membership in groups based on interest, values, and identity, not solely geography. Secondly, this allows for greater inclusivity, particularly for adolescents who experience oppression or marginalization as a result of others’ targeting them based on identity or perceived identity.

These maps are populated by what I have termed “characters” (feel free to use different terminology). “Characters” are representations of those elements that impact adolescents the most (i.e. institutions, places, events, policies). As a facilitator, I have found it helpful at this stage to engage adolescents in naming the dynamic relationships between people and other elements of a community and the meanings of such relationships.

Below is a description of the activity, with facilitator instructions.

Creating the maps

Benefits of the activity:

- Build community around shared experiences of oppression and/or shared visions of transformation

- Promote critical thinking and critical dialogue

- Identify dynamics that impact adolescents’ lives, while encouraging their self-advocacy

Framing questions to ask at the beginning, and revisit throughout to encourage dialogue:

- What comes to mind when you think of the word ‘community’?

- What do communities consist of?

- How can we understand a community?

- Are people the only entities that have stories to tell about the communities we belong to?

Step #1 – Map design

Ask participants to name a community they belong to and want to transform and/or take action in response to an inequity and/or oppression that has been individually or collectively experienced. Instruct the group to create a map that features “characters” (i.e. places, buildings, institutions, policies, rules) that comprise their community (geographical or non-geographical). Pay attention to group dynamics to ensure an equity of voices in the decisions of what gets placed on the map. For non-geographical communities, participants could use systems, policies, and/or institutions as “characters” that impact the community. Relationships and power dynamics can be shown by giving “characters” different sizes (i.e. the bank is the biggest thing on the map because of its impact on the community’s economic state).

Step #2 – Mapping the story

Introduce the word balloon for dialogue between “characters” on the map and thought bubble to see the inner thoughts of a given “character”, and explain their purposes.

Present the reflection questions below and instruct participants to use word balloons and thought bubbles to represent dialogue between the “characters” about the transformation or oppression that was identified in step #1. Reflective questions may include:

- What would each “character” say about its experience with, or observations about, the oppression or vision of transformation that was identified?

- What observations has each “character” made about the oppression or vision of transformation?

- If we could read the thoughts of each “character,” what would we learn?

Participants should then discuss the questions or other questions that may resonate with the group and write responses on the word balloons and thought bubbles. Participants can then place the shapes on the corresponding “characters” on the map.

Step #3 – Expanding the story

Introduce two tools (adapted versions of “flashback, flash-forward” and “hot-seat the character”) that the group will use to engage in critical dialogue. Prompt the group to think about what the “characters” would say if they could flashback or flash-forward in time. For example, if a park is represented on the map, a flashback question could be: what would this park have said was its experience with gentrification 10 years ago?

Next, invite a group member to “hot-seat” another “character”. Group members then get to pose questions to the “character” that are discussed as a group. The focus can be on expanding upon what was written in the word balloons/thoughts bubbles, or what was shared in the flashback and flash forward discussions. For example, a group member might “hot-seat” a group mate’s school “character” and ask: why do you want school administrators to do more to make families feel welcome in the school? Such a question, and others, could engage the group in deeper discussions about school-community relationships.

Step #4 – Processing, closing, action steps

This final step provides a way for the group to reflect on their experiences going through the activity. The group may also draw connections to potential future actions they could take related to the issues represented on their maps. I have found sitting or standing in a circle with the map inside of the circle as the most engaging way to facilitate this step.

The questions below are recommended, but are not the only ones that you could ask.

- What common themes or differences emerged during the process?

- What can we do to learn more about the community? Is there someone with whom we can talk? Is there someplace we can visit?

- Is there any action around shared visions of transformation, or shared experiences of oppression that we would like to explore?

These steps are about adolescents’ ability to make meaning of their community, and treats them as the subjects of their own learning. My experiences facilitating Community Stories have shown me that adolescents grow more comfortable discussing issues that resonate with their individual and collective identities when given the space to do so. While that can take various forms, hopefully, Community Stories will serve as another approach that you can use with adolescents who are looking to change their communities.

The views, information and opinions expressed herein are those of the author; they do not necessarily reflect those of the Council on Accreditation (COA). COA invites guest authors to contribute to the COA blog due to COA’s confidence in their knowledge on the subject matter and their expertise in their chosen field.

Ruben Mina, LMSW

Ruben Mina, LMSW, is a social work community practitioner with close to 15 years of experience in youth development and education. He currently works for the New York City Department of Education alongside an amazing group of folks who are dedicated to achieving equity for students in all schools and districts throughout New York City. His work involves leading workshops for educators on topics like implicit bias awareness, racial equity, and anti-oppression. He also works with educators at the school- and district-levels on creating equitable policies and practices. He serves on the Masters Exam Committee for the Association of Social Work Boards. As a born and bred Brooklyn native, he loves music from any and everywhere, and classic Twilight Zone episodes. He is excited to begin pursuing a doctoral degree this fall.

A big thank you to Shondelle Wills-Bryce, MSW of Sisters Keeping InTouch, inspires, LLC for this guest post!

The peace and serenity of a spring morning is undeniable. Take a moment wherever you are and observe the synergy of nature surrounding you. During my moment, I heard birds chirping, I felt the cool breeze on my arms, and I saw greenery all around. I smiled in amazement, thinking about how nature seemingly effortlessly comes together to bring us beautiful days. I then found myself perplexed about how we as people and we as professionals make “coming together” –aka partnership–so complicated.

Whether you choose to use science, religious beliefs, observation, or a combination of all three, you cannot deny that Mother Nature is the queen of partnership. According to the Oxford dictionary, nature is “the phenomena of the physical world collectively, including plants, animals, the landscape, and other features and products of the earth, as opposed to humans or human creations” (emphasis mine). Each part of nature’s collective does its job without hesitation, and as a result, the system operates successfully.

The system of nature is so effective that even when humans disrupt its natural order, the system automatically adjusts. You may call one such adjustment global warming. However, if Mother Nature could say anything about her adjustment, she might simply say, “I am getting back on track because I am clear about my job and purpose for life on earth.”

In my opinion, the words of Henry Ford describe partnership best:

So, I challenge you to ask yourself, am I clear about my job and my purpose in my partnerships?

Successful partnerships at work

In my various personal and professional roles, I have witnessed the transformational power of partnerships. Some successful partnerships are used for positive impact; others, not so much. Let’s agree to spend our time focusing on the impact and qualities of successful partnerships in order to improve our own.

The annual journal Partnership Matters examines the current thinking and practice in cross-sector partnerships. This journal was developed as a result of the growing recognition that partnerships between business, government, and civic organizations can effectively tackle the social, economic, and environmental challenges of the world. However, based on my experience “aging out” of NYC’s child welfare system, working for the New Jersey Department of Children and Families, and coaching millennial women, I would challenge the journal to include individuals, families, and communities in its examination.

NYC’s Child Welfare System

I was a timid and terrified 15-year-old when the Bureau of Child Welfare (BCW) (today known as New York City’s Administration for Children’s Services (ACS)) placed me in a Bronx group home with 21 other girls. The back story of how and why I was placed in the care of the state isn’t relevant at this time. What is relevant is how the partnerships within the child welfare system helped me become a valuable addition to society.

To wit: The hospital that admitted me did not solely care for my fractured arm.

- The hospital used a collaborative tool to ask me questions about my injury.

- The collaborative tool then triggered the hospital’s need to contact BCW for a closer look at my situation.

- BCW did not solely decide to remove me from the care of my family. BCW spoke to countless community partners (hospital, my school, my family, my neighbors, and me) to make that decision.

The evidence of this successful partnership—and all the communication that it took — was me. Although I was a terrified 15-year-old with limited exposure to the realities of the world, I did not feel lost, and I did not feel alone. After spending six years in the care of BCW, I emerged an educated, responsible, and psychologically sound member of society. That was in large part thanks to this teamwork.

NJ Department of Children and Families (DCF)

15 years after leaving the care of New York City, I began working for New Jersey’s child welfare system (the Department of Children and Families, or DCF) as its Assistant Director of School Linked Services. During my nine years with DCF, my office monitored the distribution and service delivery of $38M in state and federal funds to support school-based prevention and intervention programming. Partnership was key to DCF’s ability to serve children and families effectively, and critical to that was DCF’s strong partnership with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families (ACF).

During my last five years with DCF, my office was awarded an additional $6.5M in competitive federal funding. In addition to putting forth and strong comprehensive grant application, I am confident the historical strength and integrity of DCF’s partnership with ACF played a role in the award decision. As a result, the funds expanded services to support NJ’s expectant and parenting youth (including young fathers) with evidence based services. My office had to partner within the department, across state departments, and with the local communities throughout New Jersey:

- Partnerships within DCF included the Division of Children’s Systems of Care, the Office of Adolescent Services, the Division of Child Protection and Permanency, the Division on Women and the Division of Family and Community Partnerships.

- Formal and informal state level partnerships included NJ Department of Human Services (child support and mental health services), the NJ Department of Education, the NJ Department of Labor (employment trainings) and the NJ Department of Health.

- Local partners included community based organizations, local board of educations, universities, hospitals, and representatives of the children, youth, families, and communities targeted for these services.

I will be honest: The time to coordinate, the patience to listen, and the willingness to compromise with these partners was not always easy. However, what made it a little easier was agreed upon goals, clearly documented working agreements (MOUs/contracts), and some good old fashioned open and honest dialog.

As a result of our collaboration, DCF more than doubled its support of expectant and parenting teens from 208 (female students) to 500+ (male and female students). One of the program goals was to prevent subsequent pregnancies while students were in school. I am proud to say that the outcome data reported less than 1% subsequent in-school pregnancies.

Coaching millennial women

At the age of 21, I was no longer allowed to be dependent on NYC’s child welfare system. The system prepared me to be on my own to the best of its ability; however, there was so much I had to learn on my own. I knew if I stayed focused and made all the “right” decisions, I could make it on my own. It worked. I did it–I learned how to survive by getting my college degree and a job to pay for my basic living expenses.

I may have been 28 years old when I felt like I could pause and take a breath. The breath allowed me to no longer worry about failing and worry about what “people” would say. That breath allowed me to truly look at life for its beauty and possibilities. That breath allowed me the luxury of connecting with myself to understand my goals and purpose to thrive in life.

It was about that age that I felt that maybe, just maybe, I was thriving in life. At the same time, I knew then and I know now that there is still so much thriving for me to do. At that age, I didn’t know who in my “real” life to ask for guidance. I’m not sure I even knew to ask. I wonder if my school or the system partnered with me more, I would have known how to really thrive.

What worked for me was finding incredible virtual mentors like Maya Angelou, Oprah Winfrey, Iyanla Vanzant and Suze Orman. The character of each of these women were attractive to me because they were authentic and partnered with the world to make it a better place. Today, I look around and see my former self in young women who have amazing potential but are struggling and doubting themselves.

According Pew Research Center, millennial women (women born between 1981-1996) are better educated and hold a bachelor’s degree at a higher rate their male counterparts. I strongly believe that when the millennial woman takes leadership in her life, she will positively impact her partner, family, and community.

Therefore, approximately two years before I left DCF, I began my own personal development firm, Sisters Keeping In Touch, Inspires (SKIT). In this work, I am committed to partnering with millennial women and those who want to help them not just survive but thrive. This purpose-driven work is accomplished in partnership with millennial women through public speaking, blogging, and facilitated experiences.

In these partnership with millennial women, we work to uplift and strengthen them, so that each can build the personal and professional life of her dreams. When a woman does her building, she will avoid and/or minimize unhealthy relationships with her partner(s), children, finances, friends, and career. We work through an ART process, where she is the artist in her life:

In my work with millennial women, they have felt heard, encouraged, and connected with people and resources needed to thrive. Visit our site to see some stories of success.

These are just three examples from my world of successful partnerships. I am quite sure you have examples of successful partnerships surrounding you as well.

Closing thoughts: Recipes for success

There is an abundance of articles, journals, and opinions about what ingredients go into a successful partnership. My personal favorite is the guidance provided in Don Miguel Ruiz’s book, The Four Agreements:

These four agreements have served me well as a recipe for my success in cultivating and managing partnerships. I challenge you incorporate these agreements in your partnership relationships and experience the transformation. When you do, you may be able to replicate the clear and effective partnership synergy mother nature has shown us in all her splendor.

The views, information and opinions expressed herein are those of the author; they do not necessarily reflect those of the Council on Accreditation (COA). COA invites guest authors to contribute to the COA blog due to COA’s confidence in their knowledge on the subject matter and their expertise in their chosen field.

Shondelle C. Wills-Bryce, MSW

Shondelle C. Wills-Bryce, a master’s level administrative social worker, public speaker and conversation facilitator founded Sisters Keeping In Touch, inspires to help millennial women thrive and not just survive. Shondelle has developed personal resilience having lost her mother to Breast Cancer at 18 months and aging out of New York’s foster care system. Shondelle is the mother of two amazing young women and she is married to her husband and best friend who motivate her each day.

A big thank you to Catholic Charities of Buffalo, New York for this guest post!

We at Catholic Charities Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) Program believe that empathy can create positive change, giving WIC participants the most resources and best experiences possible to live healthier lifestyles with their families and community. Our term for this is called “Participant-Centered Nutrition Services.” With the family and their needs at the center of each interaction at WIC, we can better focus on the nutrition education and resources appropriate to suit them. With this in mind, we created the Shopping Experience Simulation.

The goals of the Shopping Experience Simulation initiative were to:

- Address the barriers encountered by WIC participants during the grocery store experience that prohibit them from using WIC checks to buy nutritious foods;

- Encourage empathy among the staff of nutritionists and nutrition assistants for our WIC families and the issues that they face when using WIC benefits;

- Increase attendance of WIC families at appointments so they may receive nutrition and health information and get referrals to other resources that are available for families in the community ; and

- Identify educational opportunities for WIC staff to improve the WIC shopping experience by providing better nutrition counseling before WIC participants go shopping.

The Shopping Experience Simulation (the Simulation) included three steps: planning, simulation, and debriefing. A team of three staff planned and coordinated all activities in the Simulation. This team met with grocery store management to plan the Simulation, created simulated WIC checks to represent all different kinds of WIC participants, and coordinated which staff would work together. In the Simulation, all WIC participant types were represented: pregnant women, breastfeeding postpartum women with infant, postpartum women formula feeding her infant, and families with toddlers and preschoolers. In the Simulation, staff in teams of two were assigned a WIC participant role, and had 30 minutes to shop with the simulated WIC checks. Immediately after the shopping experience WIC staff attended a debriefing session that included a survey, a group discussion, and a brainstorming session for takeaways.

Planning

In the planning phase, we contacted TOPS Supermarkets as the vendor partner for the Simulation. After phone conversations, we selected the local store and held a meeting with the company executive, store manager, and store management team to review the Simulation plan and establish expectations for all parties. TOPS Supermarket would supply two training checkouts and cashiers to simulate real physical check out of food items, enforcing all WIC policies concerning separating food items, signing and dating checks, and purchasing of approved items. Afterwards, store personnel would replace all simulation food items to proper place in store.

The Simulation was piloted by 13 staff from the Kenmore and North Buffalo WIC locations. Staff would be provided one month of WIC checks. Checks would represent a variety of WIC food packages, including breast feeding mother and baby, infant on specialized formula, participant-requested soy products, and a standard package for child and pregnant woman. Participating staff would have 30 minutes to purchase WIC approved foods as listed on checks, following WIC policies. Staff members were given WIC check folders and food sheets to follow and guide the experience. The staff members were not given the WIC pictorial food guide as an aid. The Store Manager was available for any questions or assistance.

Simulation

Even with all of this structure in place, reality set in. Shelves were bare where baby food should be. Aisles were crowded, and labels were difficult to find to make sure the item was correct. It took over 18 minutes for the pharmacist to unlock the baby formula case. The wait in the cashier’s line was embarrassingly long, as each item had to be checked to make sure it was as written on the check. Staff became frustrated, losing their checks in abandoned shopping carts. If children would have been added to the mix, as they are in reality, it would have been a truer simulation, and almost certainly more frustrating. To ensure an accurate reflection of the shopping experience, the WIC staff immediately completed a written debriefing questionnaire on feelings and experiences associated with the Simulation. Staff then had an opportunity to verbally share experiences and brainstorm ideas for making the shopping experience better, including how to counsel WIC participants to better prepare them for shopping and using WIC benefits.

Debriefing

The debriefing results were tallied and shared with the entire WIC Leadership Team, WIC staff, and the New York State WIC Learning Community. As a result of the Shopping Experience Simulation results, educational action steps were designed to administer this Simulation training to all 107 employees at all 21 sites across the 3 counties that we serve (the Erie, Niagara, and Chautauqua Counties in Western New York). A report with the debriefing data was then e-mailed to executives at TOPS Supermarket to share the impact the Shopping Experience Simulation would have on WIC activities. This partnership and feedback with TOPS Supermarket also generated ideas on how to make the general shopping experience better.

We took challenges in stride, and made adjustments for future Simulations. We noted that too many WIC staff participated at one time, which overwhelmed the small store and training cashiers. To lessen the impact on the store, fewer staff will be trained at one time in the future. Too many checks were given out , and it became too much to handle. In the future, one week of WIC checks will be given to each staff member.

What was learned was more valuable than the resources that went into the execution of the Simulation. This Simulation effectively used resources, as it cost virtually nothing to train the staff. The only cost associated with the Simulation was staff time. Feeling overwhelmed themselves allowed WIC staff to connect with WIC participants. Staff learned to be less judgmental, more supportive, and more open to the needs of WIC families. The WIC Shopping Experience Simulation illustrated how small but effective educational changes can provide better participant-centered nutrition services and make the work of WIC participants, WIC staff, and vendors easier through a more successful shopping experience. Empathy resulting from the experience will give WIC staff an increased capacity to respond to concerns of WIC participants and validate WIC participants’ experience and feelings while shopping with WIC checks.

Embedding lessons learned

As a result of the simulation, several changes have been made to all Catholic Charities WIC office procedures:

- All WIC staff will participate in the Shopping Experience Simulation within the next year and ongoing as more WIC staff are hired;

- All WIC support staff are providing follow-up calls to all new WIC participants, offering support and assistance in any aspect of the WIC process, including successfully using WIC benefits to purchase nutritious WIC foods;

- WIC Nutritionists will spend additional time reviewing the WIC Acceptable Food Cards, including highlighting foods preferred by WIC participants to better prepare them for their selections available when they go to the store;

- All staff will emphasize the importance of WIC check safety and importance of organization and planning in order to have a successful and stress-free shopping experience;

- The WIC Program will collaborate with Vendor Management Agency to act as liaison between the WIC Program and stores to organize simulations. This will help the planning team to accomplish a seamless process for orienting staff on the Shopping Experience Simulation; and

- To make the Simulation more realistic and to develop empathy for WIC participants with transportation issues, the Simulation in the future will include riding the bus or walking a short distance with food purchases.

The Shopping Experience Simulation accomplishes much with little investment. Catholic Charities WIC Program has shared the Shopping Experience Simulation with all other WIC Programs in New York State as an innovative practice. The original team that developed the Shopping Experience Simulation has presented the project on the state level in the WIC Learning Community and for a WIC Conference in Albany, New York. The Shopping Experience Simulation demonstrates a new way of thinking about WIC participants. Walking in their shoes through their experience creates empathy and enriched practices. This has been warmly received in the New York State WIC community. I encourage readers to ask yourself what experiences you can provide your staff to augment their understanding of your clients. Concentrate on your services. Simulating customer service experiences while following our steps of planning, simulation, and debriefing will help your staff gain client perspective. Gathering data from simulation experience will help frame action steps to make your business and services more client-friendly.

The views, information and opinions expressed herein are those of the author; they do not necessarily reflect those of the Council on Accreditation (COA). COA invites guest authors to contribute to the COA blog due to COA’s confidence in their knowledge on the subject matter and their expertise in their chosen field.

Grace McKenzie

Grace McKenzie holds a Master’s Degree in Education from Buffalo State College. For the past fifteen years, she has worked in Community Relations and Outreach for various nonprofit organizations. Currently, she works at Catholic Charities of Buffalo as the Outreach Supervisor for WIC. As a mom, she enjoys family time with her two girls, including exploring nature, tending the garden, visiting museums and family time at home.

Protect your clients, protect your staff, protect your organization, protect your community.

As the virus that causes COVID-19 continues to have a significant impact on our lives, accredited and in-process organizations have asked us how the standards can help them be ready and respond. In this post we will make a few big-picture recommendations about where to start with your preparations, then point out the key standards that might inform your response.

A few quick recommendations

Before we look at specific standards, we have a few recommendations. First, pull your senior staff and members of your governing body together to think about what your organization needs to do be prepared for and respond to the virus. We strongly recommend that you review the CDC’s Interim Guidance for Administrators and Leaders of Community- and Faith-Based Organizations to Plan, Prepare, and Respond to Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). This resource is the single best resource we have seen to help you prepare your organization for the inevitable arrival of the coronavirus in your community. The guidance provided is specific and clear and is continually updated as new information emerges.

Second, review and update your emergency preparedness plan and other relevant polices and procedures. COA has several standards that address key preparedness and response issues that accredited organizations will already have in place. These fall under the broad standards categories of human resources management, safety and security, and emergency preparedness. More about these below.

With regard to service delivery: Depending on the types of services you provide and the populations you serve, you are very likely to get multiple communications from federal, state, and county oversight entities, as well as others with specific directives and/or guidance that will directly effect your work at the program level. You will want to merge these varying sources of guidance– some of these will be mandatory–into a form that staff can understand and follow.

It is important also to make this information easily accessible. One organization that serves the homeless mentally ill in upstate New York has been receiving updated virus-related directives from multiple sources almost every other day. Every time one of these is received, the CEO merges the new information into updated procedures and then walks around and replaces the old documents, which have been posted all over the facility, with the newest version. Staff are very busy and aren’t always able to stop what they are doing and check their email to see if new updates have been made to the online procedure manual. So put such critical information right in front of them.

Third, communicate clearly and openly with the people you serve, your staff, and the public. The situation in your locale may be changing quickly. Your clients and staff will be looking to you for guidance. Wild Apricot has a very good blog entry titled How to Create a Crisis Communications Plan for Your Nonprofit that you may find useful.

Communication also includes ensuring that staff know who to go to for answers in rapidly evolving situations. Anticipate that some staff who have decision making authority may become sick. Plan for that eventuality, and make sure that staff know who to go to in their place. This is especially important in larger, multiservice organizations who may provide a variety of different services in multiple locations.

Now lets take a look at some of the key COA standards. Currently accredited organizations will have policies and procedures related to these standards already in place. For these organizations, your task it to review these and update them where necessary.

Review and update your emergency response plan and procedures

Pull out your emergency response plan and procedures (ASE 6.01, ASE 6.02, ASE 6.03) and review them with COVID-19 in mind. If you are like many other organizations, you may not have anticipated a fast-moving pandemic when your plan was developed. Emergency response plans and procedures for multiservice organizations and those providing services at different sites may need to include location-specific guidance for each program site.

Things to consider:

- Clarifying who will communicate with authorities and emergency responders at each program location

- Clarifying and testing your lines of communication to staff, your board, clients, and the public

- Clarifying your responsibilities for persons served with mobility challenges and other special needs

- Do you have sufficient supplies at each site? (I.e. masks, gloves, hand-sanitizer, first aid, first aid manuals, cleaning supplies, disinfectant, toilet paper, food, maintenance supplies, batteries, etc.)

- Is emergency contact information up-to-date for all staff and service recipients?

- Will medications be available for people in residential facilities?

- Are copies of emergency response plans and procedures readily available to staff at all program sites?

- How will programs and administrative offices cope with multiple staff absences due to illness?

- If volunteers perform important functions, how will those functions be done if volunteers are prohibited from entering your program sites?

- How will your programs operate if absenteeism spikes?

Review and update safety and security measures

The standards in ASE 5: Safety and Security address the safety and security of your staff and persons served at your program and administrative sites. Review your most recent safety assessment and any measures that were implemented to address identified issues. Then conduct a new COVID-19 assessment if time permits.

Things to consider:

- Will you need to update or create a visitor policy? (I.e., will visitors be prohibited? Who will be allowed to enter your program sites?)

- Will staff and service recipients be permitted to congregate?

- Will face-to-face staff/client interactions be permitted? If so, under what conditions?

- How quickly can you train staff on updated safety procedures and protocols?

- If you run a residential program, are you capable of quarantining residents? If not, what happens with residents who are ordered to be quarantined? How do you promote/enforce social distancing in congregate care facilities?

Review and update human resource management policies

By the time you read this, many of you will already be under restrictions mandating the closure of all non-essential businesses. Although most of our accredited organizations will be not be subject to those restrictions, most have staff that do not necessarily need to be on-site to perform their jobs. Many of you are scrambling to put human resource policies in place to reflect this new reality. The standard HR 3.02 broadly addresses what may go into an HR policies and procedure manual.

Things to consider:

- Which jobs are critical to the organization’s continued operation? Which can be performed remotely, and which cannot?

- How will critical job functions be performed if key staff are absent due to illness or the need to care for family members?

- Do you have a remote working policy? How will supervision be conducted for remote workers?

- Do your sick time and leave policies reflect guidelines and mandates about virus-related sick time? Does your family-leave time? Do they encourage staff to stay home if they feel sick?

- Is your HR department staying abreast of the latest, rapidly-changing federal and state rules about insurance costs? Are you prepared to help staff understand how new rules apply to them?

Again, the CDC has good, comprehensive, practical guidance for employers: Interim Guidance for Businesses and Employers to Plan and Respond to Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19).

Review and update technology and information security for remote working

Remote working is as much a technological issue as it is a human resources management issue. The policies and procedures required for RPM 4: Technology and Information Management, and RPM 5: Security of Information should be reviewed and updated if you will be requiring some of your staff to work at home.

Things to consider:

- How will staff securely access work files from off-site?

- How will remote staff communicate with staff who are still working onsite? With each other?

Review and update policies and procedures for technology-based service delivery

The coronavirus has rapidly pushed technology-based service delivery from the periphery to becoming a core intervention modality for many kinds of social and human services. If you are already employing technology-based interventions, take this time to review new rules and guidance coming for the federal government on its use. Then review the standards in PRG 4: Technology-based Service Delivery to ensure that your current practices continue to meet the requirements of the standards.

If you are thinking about employing technology-based interventions for the first time, you need to understand that there are many important factors to consider, including confidentially, security, data collection and transmission, acceptable technologies, licensure, how to work with clients through electronic means, and more. A review of the standards in PRG 4 will give you a frame of reference for what such services look like.

We hope this post helps to bring some of the most important questions into focus for you as you prepare for the coronavirus. The function of accreditation is to build organization’s capacity and resilience through a careful and thorough review of its administration and service-delivery practices. It does this by having you look at what you are doing and how you are doing it, thinking about how you can do things better, and, finally looking ahead so you can be ready for what is coming, both seen and unforeseen.

Be safe.

In light of the ongoing coronavirus crisis, we wanted to highlight some of the resources that we provide on our website, and to provide additional ones, as well. Stay up-to-date on everything happening with COA during the pandemic here.

No matter what role you occupy in the social service delivery continuum, chances are that precautions in the face of COVID-19 have drastically changed the way you work in just a few short weeks. This rapid transition in our lifestyles has led to a deluge of information about how to cope and behave during this time, both personally and professionally. COA has put together a list of references to assist you and your colleagues in navigating all of this news and guidance. We’ve organized the information below by topic:

- General guidance from government agencies

- Guidance for child welfare providers

- Guidance for childcare providers

- Guidance for businesses and employers

- Guidance for healthcare professionals

- Guidance for community organizations

- Guidance on reducing stigma

The Interpretation blog is meant, first and foremost, to be a resource for the COA community. We are continually evolving our blog content to meet the needs of our COA network. If you have a resource, article, or tool that you’d like to see posted, we’d love to hear from you! Reach out to us by email at PublicPolicy@coanet.org.

General guidance from government agencies

It’s important to educate yourself on and follow the guidance of international, national, and local health organizations. The following organizations maintain a collection of resources and information on the spread of COVID-19. COA recommends locating the health agency of your state or territory to find information that is specific to your local community. In addition, make sure that you are signing up for available subscription/distribution lists, where information may be disseminated on an ongoing basis.

- From the World Health Organization (WHO): Coronavirus Disease (COVID-2019) Situation Reports

- From the U.S. Center for Disease Control (CDC): Coronavirus Disease 2019

- From the Canadian Department of Health: Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19): Outbreak Update

- Directory of state and territory health agencies

Guidance for child welfare providers

The US Children’s Bureau shared this letter with the agencies they oversee the in child welfare system. In addition to this letter, the Children’s Bureau is maintaining this webpage with resources related to COVID-19.

Organizations leading the field in child welfare practice and policy have also created resources to assist agencies in navigating service delivery during this time:

- From the National Child Traumatic Stress Network: Parent/Caregiver Guide to Helping Families Cope with the Coronavirus Disease

- From Generations United: COVID-19 Fact Sheet for Grandfamilies and Multigenerational Families

- From Prevent Child Abuse America: Coronavirus Resources & Tips for Parents, Children & Others

- From the National Association of Social Workers: Resources for Social Workers

In addition, The Chronicle of Social Change (now The Imprint) has redirected their reporting to focus on COVID-19 and have posted a number of stories on developments in the child welfare space. We recommend starting with Coronavirus: What Child Welfare Systems Need to Think About.

Guidance for childcare providers

Childcare providers have been deemed essential workers across many regions, even areas with the strictest social distancing regulations in place. This is because we need to ensure childcare is accessible to other essential workers during this time.

Guidance for businesses and employers

There is no doubt that concerns about and restrictions around COVID-19 are impacting how businesses are run. We’ve seen some guidance on how to bear out these changes here:

- From the CDC: Resources for Businesses and Employers

- From the US Department of Labor: COVID-19 Overview

- From the National Council on Nonprofits: The Nonprofit Community Confronts the Coronavirus

Guidance for healthcare professionals

Healthcare facilities are on the front lines of the COVID-19 pandemic. Find resources to help manage resources and protect yourself and your staff below.

- From the CDC: Resources for Clinics and Healthcare Facilities

- From the CDC: Resources for Healthcare Professionals

Guidance for community organizations

Community-based organizations will be integral to ensuring the infrastructure of community needs are able to be met during this time. Fortunately, there are COVID-19 tools available for organizations that serve vulnerable populations:

- From the CDC: Resources for Community- and Faith-Based Leaders

- From the CDC: Resources to Support People Experiencing Homelessness

The National Coalition for Homeless Veterans also has resources specific to each type of services provider they oversee:

- From the National Coalition for Homeless Veterans: COVID-19 Resources

Guidance on reducing stigma

Stigma affects the emotional and mental health of those that the stigma is directed against. Stopping stigma is an important part of making communities and community members resilient during public health emergencies. Even if we are not personally involved with the stigmatized groups, our voice can have an impact.

- From the CDC: Reducing Stigma During a Public Health Crisis

What other helpful resources for managing the COVID-19 outbreak have you seen? Share yours in the comments below.

Thank you to Avi Rudnick, JD, MSW of Chicago House for this guest post!

In the early years of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the U.S., nearly 100 activists met at the historic Baton Show Lounge to address the dire need for housing for Chicagoans living with AIDS; out of this Chicago House and Social Service Agency was borne as a not-for-profit providing a compassionate response to the disease. Chicago House serves individuals and families who are disenfranchised by HIV/AIDS, LGBTQ marginalization, poverty, homelessness, and/or gender nonconformity. Most of the individuals served have received messages in the past from family and friends that increase shame and stigma regarding behaviors and health status, which can result in a disengagement from services. It was important for Chicago House to choose a service philosophy that helped meet the service recipient where they’re at. Enter harm reduction.

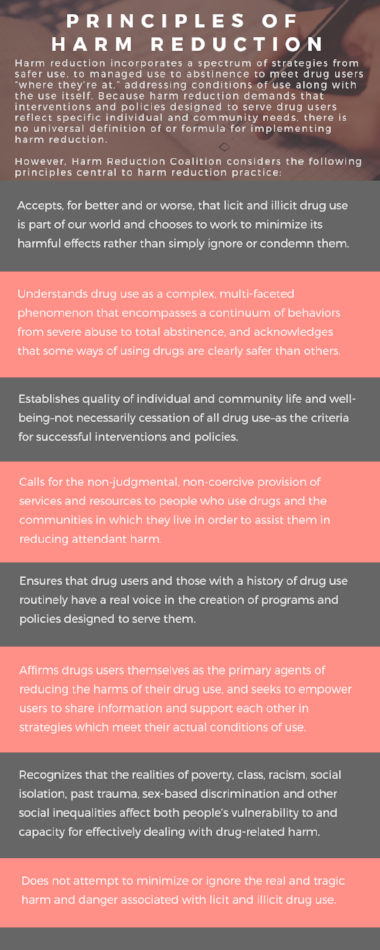

What is harm reduction?

Harm reduction is a client-centered, trauma-informed approach that emphasizes safety and client self-determination. The philosophy dates back to work being done by activists, doctors, programs, and policy-makers in the 1960s and 70s as legal systems all over the globe began to take punitive measures against drugs. An early adopter of the philosophy was the Netherlands who put together commissions assessing whether strict law enforcement was best practice, referring to it as a “balance of harms.” It wasn’t until the 1980s that the collective efforts began to be referred to as harm reduction.

Harm reduction treats the individual as the expert in their own life, service recipients are given the agency to determine whether or how they want to change behavior. While harm reduction does not promote risky behavior, it also does not mandate sobriety as a barometer of success. A concrete example of how this plays out in the real world would be needle exchange programs. Needle exchange programs provide a safe, non-judgmental space for intravenous drug users to exchange their used needles for clean ones. They have been shown to significantly reduce the spread of blood-borne pathogens, such as hepatitis and HIV and, in fact, are associated with increased participation in treatment programs. Instead of focusing energy on the individuals’ sobriety, the programs provide resources to prevent the spread of disease and create a safe space for users. In addition to utilizing harm reduction approaches for addressing substance use, harm reduction is a philosophy that can be applied to many aspects of individual and community life, including, but not limited to: housing, health care, intimate partner violence, and mental health.

Why this philosophy works for Chicago House

Given the individuals served by Chicago House’s marginalized identities, it is not infrequent that one of the earliest and first hurtles is simply earning their trust and building rapport, that is Chicago House’s service providers’ first task. By prioritizing that relationship and putting the individual as the expert in their own life, the service providers help to even out the natural power dynamic that occurs and puts the individual at ease. Together the client and service provider can then explore the individual’s reasons for engaging in high risk behaviors and develop strategies and motivation to engage in safer behaviors (such as engaging in primary care and going on Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis). They inventory the individual’s coping mechanisms and enhance them. Harm reduction supports any positive change, thus putting the individual at ease that they are in a safe space.

Another reason harm reduction makes for a strong service philosophy for the population Chicago House serves is its relationship with trauma-informed care. Most of the clients served by Chicago House and Social Service Agency have experienced some form of trauma in their lives, so it is both fitting and necessary that the agency’s philosophy of care includes a trauma-informed approach to services. Client behavior is considered through the lens of someone who has experienced trauma and is honored as a coping and survival skill, highlighting the clients’ resiliency and ability to adapt which dovetails nicely with harm reduction’s strengths-based approach. Staff members work with clients to establish and maintain a sense of safety and mastery in their environment, something that is often times difficult for individuals with a trauma history, and recognize this as a basic building block for all other interventions.

Implementing harm reduction during service planning

Harm reduction philosophies are infused in the service planning process with clients and work to establish realistic goals regarding housing, health care, income, employment, education, substance use, mental health, etc. Chicago House approaches the creation of service plans with clients as a collaborative process, centering the client as the expert of their own life. While our funders may require that we include certain categories in our service plans, we work with clients on an ongoing basis to develop objectives and strategies to accomplish their goals. For some clients, a goal may be scheduling and attending an appointment with their HIV provider within the next six months, studying for the math portion of the GED exam, or going to the public aid office to apply for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program.

Utilizing a collaborative harm reduction approach allows for changes in life circumstances and for our clients to move through the stages of change without being on the receiving end of shame inducing program requirements that increase fear and the possibility of discharge from programming. If a client does not achieve their goal within the six months outlined in the service plan, case managers use the opportunity to try different interventions, assisting the client in identifying strengths and new possibilities for different goals or a different approach to achieving the existing goal.

Harm reduction-related professional development

Chicago House regularly provides staff with professional development opportunities, such as brown bag lunches. One topic they facilitated recently was Sex Work: Reducing Stigma and Shame. Many of Chicago House’s clients have or are currently engaged in sex work. Instead of asking them to stop or making them feel bad about their choices, providers are being taught about the experience of sex workers so that they are more equipped to support the service recipients.

During this brown bag, staff watched a video of a Ted Talk presented by Juno Mac. She is a sex work activist who fights for sex worker rights and decriminalization of sex work. The discussion was centered on the implications of sex work for specific communities, particularly for trans women of color. Staff reviewed the report, Minority Stress and Sex Work-Understanding Stress and Internalized Stigma by the Sex Workers outreach Program (SWOP) as well as the National Transgender Discrimination Survey, Meaningful Work: Transgender Experiences in the Sex Trade. The brown bag talk wrapped up by reviewing the SWOP guide, Screening 101: Introductory Advice on Why Screening is Important and Some Basic Tips for Avoiding Bad Dates. This screening tool is information that can be directly relayed to the individuals served, providing strategies for reducing harm when engaging in sex work.

Additionally, all new staff members at Chicago House participate in a six-month philosophies of care training series, that includes an in-depth curriculum on harm reduction approaches, with two of the six sessions dedicated to trauma-informed care and motivational interviewing. All program staff members begin this training program within the first three months of employment for a total 12 hours of training on harm reduction approaches.

How other organizations can integrate harm reduction

- Develop and implement ongoing trainings for program staff and administration on harm reduction and related philosophies, such as trauma-informed care and strengths-based approaches.

- Infuse harm reduction language in all policies and procedures, reassessments, service plans, and psychosocial assessments, ensuring to eliminate language that can increase shame and stigma (i.e. not using the terms “clean” and “dirty” when referring to substance use).

- Eliminate the possibility of discharge or ineligibility based upon substance use, sex work, and/or criminal background by focusing on behavior and not stigmatized labels and identities.

The views, information and opinions expressed herein are those of the author; they do not necessarily reflect those of the Council on Accreditation (COA). COA invites guest authors to contribute to the COA blog due to COA’s confidence in their knowledge on the subject matter and their expertise in their chosen field.

Avi Rudnick

Avi Rudnick, JD, MSW began his time at Chicago House and Social Service Agency as a supportive housing case manager in July 2013. Avi stepped into the role of Director of Scattered-Site Housing in February 2016. Avi also facilitates trainings for program staff on harm reduction, trauma informed-care and motivational interviewing. In addition to his role at Chicago House, Avi has been the coordinator of the monthly Name Change Mobilization at the Transformative Justice Law Project of Illinois since 2012. Prior to working at Chicago House and his involvement with TJLP Avi worked as a public defender in Portland, Oregon.

We are all impacted by government spending and regulations beyond our day-to-day work in human services. Regulations empower us as consumers to make informed decisions about our health and safety. They give us peace of mind as employees, that our employer’s practices will be fair and that public spaces will be clean and meet the necessary standards.

We put faith in our political representatives to advance regulation in order to improve the overall welfare of our society. Over time we observe reactive regulation created to address urgent events, gradual regulation to help move the needle on key issues across a country, and preemptive regulation intended to aid the success of future generations.

Let’s explore the role of government regulations and learn more about their value to human services:

Need drives change

First, let’s discuss a historic example of the need for regulation. In September 1982, 12 year-old Mary Kellerman of Elk Grove Village, Illinois, died after consuming a capsule of extra-strength Tylenol. Within a month six more people in the vicinity would be dead and over 100 million dollars’ worth of Tylenol would be recalled from shelves across the United States. These instances amounted to what would be known as the Chicago Tylenol Murders.

The still unidentified perpetrator was purchasing Tylenol in the Chicago area, adding cyanide to the capsules, and returning them to the store. In turn the store was restocking shelves with the returned product and those that purchased and ingested the Tylenol died within an hour of consumption. Johnson & Johnson, maker of Tylenol, distributed warnings to hospitals and distributors and halted Tylenol production and advertising. Police drove through the streets of Chicago using megaphones to warn residents about the use of Tylenol.

In 1983, in response to the incident, Congress passed the Federal Anti-Tampering Bill, also known as the “Tylenol Bill”. The bill made it a federal offense to maliciously cause or attempt to cause injury or death to any person, or injury to any business’ reputation, by adulterating a food, drug, cosmetic, hazardous substance or other product. It also created a FDA requirement that all medications be sold in packaging with tamper-resistant technology.

In the face of a terrifying public safety situation, urgent government regulation was able to ease fears and create a foundation for the way medication is regulated in the U.S. today.

Regulation and our families

An example of regulatory oversight within the human services field is the passage of the Family First Prevention Services Act (FFPSA) by the U.S. Congress in 2018. It marks the largest reform of child welfare financing that has occurred in the past decade. The goal of the child welfare system is to keep all children and youth safe. The regulatory and spending path to deliver that safety has forever been changed because of this legislation.

Today it would be rare to find a human services professional that does not feel the primary initial goal for child placement is reunification with a parent or family member. Acknowledging that to keep kids safe in the long-term we must support families and alleviate issues that may lead to unsafe conditions/removal is widely accepted as best practice. The passage of FFPSA codifies this practice into law and allows funds to be used for family strengthening/preventative practices in child welfare agencies. This is a shift from exclusively funding out-of-home placement, which somewhat incentivized and eased this type of placement.

Though the enactment of FFPSA is a giant leap forward for the field, requiring some states and agencies to change decades of practices and redefining the way we regulate and implement a government program, the overall goal remains the same: to keep all children and youth safe.

Accreditation, a piece of the regulatory puzzle

Accreditation standards serve as a vehicle to implement and verify best practices. COA accreditation is recognized in over 300 instances across the US and Canada as an indicator of quality. In some cases the journey towards accreditation is due to a mandate, which is when states require that certain types of organizations become accredited. Another motivation for seeking accreditation might be due to deemed status, which is when state licensing bodies allow service providers to provide proof of accreditation in lieu of undergoing certain parts of the licensing process. The practice of states/provinces recognizing accrediting bodies is one way that they implement regulation, oversee services, and work to increase quality of services. We recommend checking out the blog post, Help! I’m Mandated! Now What? Choosing an Accreditor to learn more about navigating this topic.

Over time standards are updated to reflect advances in the field, changes in research and practice, quality indicators, and shifts in government regulation. Throughout an organization’s accreditation cycles they are able to evolve with these changes. Accreditation requires that organizations engage their stakeholders, creating an environment for services to adapt alongside the needs of the community. This relationship between accreditors, regulators, and service organizations builds a foundation for continuous quality improvement for both entities, improving outcomes for the clients served.

Conclusion

Instead of approaching government regulations as just another requirement, step back and imagine how they can assist with meeting your organization’s mission. How can these directives support your long-term goals or bolster best practice? As outlined through these examples, regulation is often born out of necessity. These rules can determine a health outcome, the safety of and access to medication, and the path for a child in foster care. At times regulation might seem like another hoop to jump through but in fact it can be a valuable component to your quality assurance toolkit.

In the high-intensity, resource-scarce universe of human services, the service environment itself often gets overlooked, or else overshadowed by compliance concerns. Against the backdrop of serving families at risk, individuals in crisis, and struggling communities, all while trying to keep the doors open, space planning concerns like layout, furnishings, lighting, and décor can seem trivial. Facility design might sound like a luxury, but in reality it has a presence in almost every aspect of service delivery. The evidence is clear. The physical environment can have a profound impact on behavior, mood, perception, and accessibility. When designed intentionally and strategically, your facility can support the work and mission of the organization. Left unexamined, it can limit or even undercut your impact.

Whether you’re opening a new site, considering a relocation, planning a renovation, or just looking for ways to refresh your facility in a way that improves the effectiveness of your services, here are some important issues to consider:

Safe space

The most fundamental concern for every organization is safety. Every facility has to comply with building codes and regulations aimed at protecting occupants from hazardous conditions. Features like emergency exits are specifically designed to promote safety by influencing behavior in the event of a critical incident – such as evacuating during a fire.

Serving vulnerable populations, however, often means preparing for and responding to critical incidents stemming from distress, conflict, and harmful behavior. In recent years suicide prevention has become a focal point for facility planners and is emerging now as a powerful example of how the built environment can be leveraged to save lives. Organizations serving populations at risk for suicide are embracing the imperative to scrutinize all architectural features, fixtures, and materials in the service environment for their potential to become an instrument for harm – specifically as an anchor point or ligature. Shatterproof glass, round-edged doors and tables, breakaway curtain and closet rods, and tamperproof power outlets are just a few examples of features that have been designed to be suicide-resistant. The layout of the service environment can also play a role in reducing opportunities to self-harm; placing staff areas in close proximity to high-risk individuals allows for consistent yet non-intrusive observation.

A trauma-informed approach tells us that identifying and addressing triggers or trauma reminders is key to preventing and de-escalating crisis situations. Organizations must examine both the physical and psychological safety of their facilities and keep in mind that the built environment itself can be a trigger or stressor. An enclosed, restrictive space can often be triggering for individuals with trauma histories or individuals with certain mental disorders, such as schizophrenia; this is often addressed by foregoing corridor layouts and installing glass doors that enable individuals to get a clear view from one service area into the next. Planners also often avoid using the color red to avoid associations with blood, fire, and emergency lights that can trigger a trauma response. Individuals coping with anxiety or PTSD can be overstimulated by patterns, brightly contrasting colors, or other visually complex designs; neutral or softer colors with more subtle transitions are therefore generally more appropriate for therapeutic environments.

While safety is imperative, there are plenty of other ways the built environment intersects with organizational goals and priorities. Now that we’ve looked at how the physical environment can reduce suicide, harmful behaviors, stress, and aggression, we can turn to how it can reinforce and encourage positive behavior and promote better client outcomes.

The client experience

A well-planned facility should complement your organization’s work by ensuring that individuals and families feel safe, supported, and in control while they are receiving services. To learn more about how organizations use the built environment to support their work, we spoke with Children’s Institute, Inc. (CII) in Los Angeles, a COA-accredited organization that provides a broad array of mental health, early care and education, child welfare, family support, and youth development services to children and families – who are also currently in the process of relocating one of their sites and constructing a new campus.

A client-centered approach informs many of the crucial decisions CII has made in identifying and designing their new facilities. “We thought about how it would affect the client’s experience, being on one floors or two,” says COO/CFO Eugene Straub. CII has been careful to ensure that their facilities are welcoming to both clients and staff. “The goal is building a sense of trust and security. The last thing you want to do is make anyone feel uneasy.” Improvements have also been made to existing sites where the space was not meeting families’ needs. “We had a nice lobby and waiting areas but there were no activities, and we looked for ways to change that and make the space more inviting and inspiring.” Now CII’s once-empty waiting areas include a lending library and creative space for children and families to use.

What are some ways that your organization could find inspiration and ideas when planning facilities? Your service recipients, staff and community are a great resource for ideas and a great place to start. Organizations should always look to their service recipients and their communities for ways to enhance their service environment, and tailor their facilities to the unique needs of the service population and to their service model. For example, a residential facility for individuals with schizophrenia can provide some relief to residents coping with paranoia by orienting beds and desks to face the door. A youth development program for children with autism spectrum disorder, who often struggle with spatial navigation and wayfinding, should consider applying visual cues to transitional spaces. Every organization’s approach to designing an effective and supportive service environment will be unique and depend on their scope, service population, service model, and culture. But there are a few universal design features that facility designers and environmental psychologists agree contribute to a calming, welcoming, and therapeutic service environment:

Nature equals nurture

Studies have consistently shown that access to nature, whether physical or visual, has a calming effect. Treatment facilities often situate themselves in a natural setting for this reason, but any organization can look to existing assets to bring to their full potential, such as a small outdoor space that can be converted into a courtyard or garden, or installing windows to take advantage of a good view. Organizations that are truly limited can still make enhancements by incorporating plant life into the decor and displaying nature and landscape art, which have also been demonstrated to have a positive and calming effect on mood.

Let the sun shine