Benchmark reports are increasingly common in the human services sector, but how do you know if this data is valuable to your organization? This blog post provides an overview of benchmarking and tips for evaluating the quality of benchmark data available to you.

What does a bench have to do with it?

Not much – unless you’re a craftsperson in antiquity. The term benchmark comes from the marks made on wooden workbenches to indicate shoe size (for cobblers), the length of board needed (for carpenters), etc. Today, a benchmark is a summary calculation – typically an average or median – which attempts to tell us what is normal for a metric.

Benchmarking within the human services sector usually comes in 3 flavors:

- Outcomes benchmarks are complex measures of change in behavior, thinking, or status. Examples include permanency in child welfare systems (such as these dashboards from the Minnesota Department of Human Services) or abstinence rate/reduction in use measures in substance use disorder treatment services. They speak to the success of a program, service, or intervention.

- Administration and management benchmarks are measures of organizational health and stability and target human resource management, financial management, governance, and similar activities. Related metrics speak to the foundational elements of an organization on which quality service delivery depends, and include staff retention rate, months cash on hand, or average board attendance rate.

- Fundraising/development benchmarks are measures of marketing and development success and efficiency. Examples include the open rate of an email seeking donations or giving rates by demographic categories. These benchmarks are the most commonly available (often at a price) as they are standard in marketing software solutions and easy to calculate and share.

What makes a good benchmark?

A benchmark is composed of 3 basic elements: the metric, the benchmark value, and the comparison group. You will need a strong definition of each to determine the value of a benchmark to your organization and should expect any quality benchmark report to outline them.

The metric

The metric should be clearly defined with a title, description, purpose, time period, and the underlying formula. Let’s use a common Human Resources measure, staff turnover, as an example:

Staff turnover is the rate of employees who leave an organization and are replaced by new employees in the stated fiscal year. This measure demonstrates an organization’s ability to maintain a stable and qualified workforce and is calculated as: (Total number of employees at the start of the fiscal year minus the total number of employees who left) divided by the total number of employees at the start of the fiscal year.

A well-defined metric is a strong indicator that all participating organizations calculated their figure consistently.

The benchmark value

This is the summary calculation and is typically an average, median, or—occasionally —a range of the sample. Here is a description of each:

- The average or mean is the “typical” value in the data. The average is only appropriate for data with a normal distribution (the bell curve shape) and is sensitive to outliers in the data.

- The median is the middle value in the data. It is less susceptible to outliers and appropriate for data with a non-normal distribution. Not sure what a normal or non-normal distribution is? No worries! The average and median will be extremely close if the data has a normal distribution, so—in any case—the median is always a safe bet.

- A full set of descriptive statistics provide a nuanced but complex view of the data’s distribution; it is the most illustrative method of describing benchmark data but can easily overwhelm most readers. These calculations can include: minimum value, maximum value, average, median, standard deviation, quartiles/percentiles, and the interquartile range.

The comparison group

The comparison group is comprised of the organizations participating in the benchmarking project. Understanding the comparison group is more than knowing the number of organizations which submitted data to the project; their overall demographic profile is the best way to assess the benchmark’s value to your organization.

What is the value of a staff turnover benchmark to a substance use treatment organization if the benchmark was generated using data from 100 arts nonprofits? A benchmark is only as valuable as its comparison integrity: the extent to which the comparison group matches the organization utilizing the benchmark to contextualize its performance. And this is what makes quality benchmarking so difficult.

A well-defined comparison group allows you to gauge the relevance of the benchmark to your organization. To have any value, a benchmarking project must collect a variety of demographic data about the participating organizations. Typical variables include:

- Revenue/budget amount: a general measure of organization size; other measures can include workforce size or average clients served per year

- Location: city, state, region, and/or community types such as urban, suburban, and rural

- Services provided: anywhere from general service categories (child welfare, behavioral health, etc.) to specific program models; this is exceptionally difficult because there are few taxonomies (systems of categorization) for human services

Why is a good benchmark so hard to find?

Generating high-quality benchmark data is a complex, time-consuming task, and, for many benchmarking projects, there is no guarantee of success. A benchmarking project requires the following.

The participants

As stressed above, coding the demographic characteristics of participating organizations is paramount. Other demographic variables typically include organization size (determined by revenue or employee count), location (region, state, and/or city), types of clients served (age, needs, or similar), and – principally – the types of services provided by the organization.

Unfortunately, the only ubiquitous, standardized method of coding human services organizations by services provided comes from the National Taxonomy of Exempt Entities (NTEE) code assigned to all tax-exempt organizations by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS); see a complete list here. However, because this code is determined solely by the IRS, it may not accurately reflect the organization’s actual services.

Well-defined, desirable metrics

The entity leading the benchmarking project must identify commonly-accepted metrics for which participating organizations see a valuable ROI. There must be clear definitions and calculation steps for each metric (yes, the dreaded data dictionary), and participating organizations must agree on their value.

Two-way reporting system

Participating organizations must have a way to provide their data and receive a benchmark report in return. Ideally, this benchmark report is dynamic and displays the data submitted by the organization side-by-side with the benchmark figure.

Quality assurance system

The system to collect and store data must have quality assurance checks to both prevent bad data from entering and identify bad data if it circumvents initial safeguards.

Longitudinal data

The best benchmarking projects will repeat their procedure on a regular schedule and collect data from the same group of participating organizations, or a fluid group of participating organizations with similar demographic characteristics.

Why utilize benchmark data?

There are 4 great reasons to seek out external benchmark data relevant to your organization.

1. Share your success with clients, grant-makers, regulators, and your Board of Trustees

These folks love data, and you love contextualizing your performance. Enriching your reports with external benchmark data can further highlight your successes, pad seemingly-poor performance (“Our turnover rate has risen but is still well under industry benchmarks”), and demonstrate your love of data and participation in the human services world beyond your walls.

2. Feed your performance and quality improvement system

A rich, enmeshed performance and quality improvement (PQI) system is the cornerstone of the Council on Accreditation’s standards and process. From the PQI standard itself:

COA’s Performance and Quality Improvement (PQI) standards provide the framework for implementation of a sustainable, organization-wide PQI system that increases the organization’s capacity to make data-informed decisions that support achievement of performance targets, program goals, positive client outcomes, and staff and client satisfaction. Building and sustaining a comprehensive, mission-driven PQI system is dependent upon the active engagement of staff from all departments of the organization, persons served, and other stakeholders throughout the improvement cycle.

Your organization is likely benchmarking performance already – that is, anytime you look to past performance to evaluate current performance. But finding benchmarks derived from peer organizations further contextualizes performance and pulls your organization out of the limited, sometimes-myopic world of its own data.

3. Get folks talking!

If you use dashboards, you’re probably seeing the same data every day. The line rises; the line falls. The number goes red; the number goes green. Over time, familiarity with the trends in your data can be desensitizing. You understand what is normal and what is not – but all of this happens within the insular universe of your organization.

External benchmark data – and particularly longitudinal benchmark data – gives more context to performance and can reinvigorate data-informed conversations which have faded over time.

4. Set goals and acknowledge high performance

Your performance and quality improvement system craves goals as a driver of performance. External benchmark data can be a powerful tool for pushing staff/programs, but this data can also further celebrate staff/programs performing above the benchmark.

What has been your experience with benchmark data?

Tell us your favorite sources of benchmark data or how you’ve integrated it into your organization’s operations in the comments below!

When it comes to serving communities and responding to individuals in crisis, law enforcement agencies and human service systems each play a role in maintaining the safety and stability of their communities. Substance use, child welfare, intimate partner violence, suicide, juvenile justice, mass violence — these are not only some of the most prominent societal challenges we face today, but also circumstances where both police officers and human service professionals are on the front lines.

The roles of law enforcement and human service agencies therefore consistently overlap. In communities and environments where needs are intensified and resources limited, this overlap comes into sharper focus. When behavioral healthcare is inaccessible, or social service systems are overburdened, communities often turn to law enforcement to fill in the gaps — sometimes leading to serious negative outcomes that can inflict trauma, injury, or death:

- Foster youth arrested and handcuffed for running away

- Mental illness played a role in 25% of fatal police shootings in 2017

- Misunderstanding disability leads to police violence

Such incidents are not only harmful to the individuals involved, but can also irrevocably damage a community’s trust in its police force and social support systems. These trends are a clear indicator that communication and partnerships between law enforcement agencies and human service providers need to be examined and strengthened.

Collaborative approaches to crisis intervention

The relationship between behavioral health and policing cannot be overstated; according to the National Alliance on Mental Illness, individuals in mental health crisis are far more likely to be confronted by police than to receive medical attention. More than 90% of patrol officers encounter individuals in crisis, with an average of 6 encounters per officer per month, but officers are often unprepared to meet the unique challenges of de-escalating a person with a disability or mental illness in crisis. A traditional law enforcement approach — “command and control,” — designed for crime intervention is likely to elicit fear and disorientation in individuals with disabilities or who are in emotional distress. Such approaches pose a significant risk of triggering a trauma response and escalating the dangerous behavior, increasing the likelihood for excessive force to be deployed.

In response to these challenges, law enforcement agencies have increasingly recognized the value of diversifying capacity and expanding officers’ skill sets in order to increase safety and efficacy in crisis response. In addition to ramping up efforts to educate officers on trauma, mental illness, and disability, and expanding training on de-escalation and crisis intervention techniques, many departments are adopting innovative new models to partner with behavioral health and human service professionals in police work.

Crisis Intervention Teams are one popular model in use in 2,700 communities across the country. The core components include recruiting, selecting, and training officers to serve as designated responders to mental health crises, and establishing relationships with a designated mental health receiving facility and other resources in the community to facilitate immediate emergency entry into the mental health system and reduce barriers to care. Officers receive 40 hours of intensive training on common disorders, developmental disability, and crisis de-escalation skills. Key to the success of this model are: ensuring adequate staffing to maintain continuous CIT coverage, equipping emergency dispatchers with the skills needed to identify when a CIT response is appropriate, and designing and delivering training curricula with the collective input of law enforcement, behavioral health specialists, and advocates. Evaluation of the CIT model indicates that it yields positive results, reducing officer injuries as well as the need for more intensive and costly law enforcement responses as well as increased referrals to emergency health care and accessibility of mental health services.

Co-responder programs are another partnership strategy with growing interest. Los Angeles, Omaha, Mesa, Arizona, and Huntington, West Virginia are among the jurisdictions that are adopting or expanding programs in 2019 to embed therapists, social workers, or addiction counselors into police departments. There is no standardized model, and program scope varies widely from place to place: some departments hire behavioral health specialists directly while others coordinate part-time or rotating coverage from a local provider; some target suicide and others substance use; they may be first on the scene or “secondary responders”; responsibilities can range from emergency response, community patrol, or even follow-up and case management. Although the programs are incredibly diverse, the rapid rate of adoption points to a culture shift in law enforcement: an emerging understanding of the agency’s role in responding to complex issues facing their communities, willingness and recognition of the value of working closely with human service professionals, and an investment towards diverting individuals in crisis away from the criminal justice system.

Establishing boundaries

Responding to individuals in crisis in the community is not the only circumstance where law enforcement and human services intersect. Although the integration of social workers and therapists into the world of community policing is a growing trend, for many human service providers — especially resource-starved ones — engaging police departments for assistance is standard operating procedure that may come with unintended consequences.

In a May 2019 lawsuit filed against the Administration for Children’s Services, the New York state appellate court ruled that family courts do not have the authority to issue warrants for foster youth who have run away from their placements — a longstanding practice. In 2017, the child welfare agency was granted 69 arrest warrants for children in their care; that was after guidelines for seeking warrants were tightened in 2015, when the number of arrest warrants issued was up to 125. In a majority of these cases, police officers deployed to retrieve missing youth end up putting them in handcuffs and in jail cells, regardless of safety risk.

Runaway behavior in foster care can often be attributed to trauma — children leave their foster care placements to be with the family members from whom they’ve been separated or other loved ones, or due to conflict with their foster parents. Being apprehended and even restrained by police officers and forcibly returned to settings where they may not feel safe exponentially compounds that trauma. The already fragile (or absent) trust in the child welfare agency may be eroded, often irrevocably, and the agency’s motivation may be perceived as punitive vs. protective.

In congregate care, the intensive needs and challenging behaviors of residents can often overwhelm the capacity of personnel and for many residential facilities, a common response to harmful or disruptive behavior, or unauthorized leave, is to summon police officers. In some communities, police departments report responding to struggling facilities multiple times a day. As with crises that take place in the community, the consequences of calling the police can be significant if the appropriate skills and protocols are not in place. And for organizations, chronic reliance on police intervention poses additional risks: therapeutic setbacks to service recipients involved, damaged staff morale, and diminished perception in the eyes of the host community and collaborating providers.

In 2015, California passed legislation aimed at reducing the frequency of law enforcement intervention in group homes and other residential facilities for children and youth. But policy or regulation is unlikely to be effective if the underlying causes are sidestepped. Experts argue that frequent calls to law enforcement are an indicator of deeper issues: inadequate staffing, insufficient training, ineffective programming, or a need to reassess admission/screening criteria. The continuum of challenges endemic to social services — underfunding, understaffing, burnout, turnover — hamper providers’ ability to meet the needs of their service population and maintain a safe and stable therapeutic environment.

If police intervention is unavoidable, then effective collaboration and proper training is critical. Providers and police departments must ensure that responding officers are familiar with the characteristics and needs of the service population and learn the skills necessary to safely de-escalate, retrieve, restrain a service recipient utilizing the least restrictive response to maintain safety. Recommendations from advocates include:

- Jointly evaluating policies and protocols to emergency response

- Creating Memoranda of Understanding between police departments and providers to better define roles and expectations around interventions, and ensure that responding officers are given relevant details about the residents in crisis

- Better data collection and analysis on the frequency and nature of law enforcement intervention in treatment settings

Children’s Village, a COA-accredited provider in New York, has called upon city leaders to form a Runaway Youth Taskforce to bring together law enforcement and social services in developing a new model for preventing and responding to runaway youth.

Meeting the mental health needs of police officers

A recent cluster of officer deaths by suicide has shed a harsh light on the challenges of addressing the mental health needs of the law enforcement community. Officers are at increased risk of PTSD, depression, anxiety, substance use, and suicide due to constant threat of violence or actual violence and exposure to death and trauma, in addition to chronic work stressors such as sleep deprivation and fatigue. Although repeatedly acknowledged by law enforcement agencies and police union leadership, the mental wellness needs of police officers are still persistently unaddressed. The culture of law enforcement has often been cited as a major barrier to care, with officers reporting fear of perception of weakness, alienation from fellow officers, and other potential professional repercussions as a result of seeking out needed services and supports.

Ignoring the mental health of police officers puts communities at risk. Studies have linked PTSD with impaired decision making ability — a critical implication for police officers in potentially life-threatening situations, and the potential for excessive or deadly force. These incidents not only increase the risk of injury or fatality of those involved, but also negatively impact the relationship between the community and law enforcement.

The human services field may be uniquely positioned to make a positive impact in this area. Professional staff in the social services and behavioral health field share many of the same work stressors as police officers — excessive caseloads, exposure to traumatic events, vulnerability in the community or service environment — and the impact of secondary or vicarious trauma has become a prominent area of research and advocacy in the human services field. Providers can bring significant knowledge to the table for law enforcement agencies about identifying and mitigating the effects of PTSD and secondary trauma, appropriate resources for treatment and support, and strategies for bolstering officers’ resilience.

Increasing the presence of behavioral health professionals in law enforcement settings can provide multiple benefits — not only by distributing or diverting the “social work” attributes of community policing, but also by providing an avenue for officers to seek support and referral to available services. Law enforcement leaders might also consider whether services provided outside of the auspices of the law enforcement agency might be more accessible to officers, potentially reinforcing confidentiality of services and softening the impact of stigma. Service providers can also assess opportunities to expand or tailor their service array in a way that focuses on the unmet needs of this population or supports their families. Research suggests that cultural competency — awareness of and responsiveness to the cultural and professional idiosyncrasies of police work — is pivotal to the accessibility and efficacy of psychological interventions targeted at police officers, and may be enhanced through peer-driven program design.

To protect and serve — and partner

Communities today are recognizing that the most pervasive social and public health challenges they are confronted with cannot be overcome without constructive collaboration between the social service, behavioral health, and criminal justice systems. Successful collaboration hinges, however, on meaningful assessment of areas of strength and need, clearly delineated roles and responsibilities, and a shared commitment to invest in the most effective solutions. Many agencies are developing or pursuing creative strategies to build partnerships between providers and police officers, with the understanding that joining forces is imperative to forming a greater understanding and capacity to meet the needs of their shared community, strengthening public trust and improving outcomes across all systems.

We’d love to hear from any organizations with experience in human services – law enforcement collaboration. Please share any promising practices or lessons learned in the comments below.

Learn more or get involved

- International Association of Chiefs of Police: One Mind Campaign

- Vera Institute of Justice: Serving Safely initiative

- National Alliance on Mental Illness: Resources for law enforcement officers

At COA, volunteerism is the thread that binds us together and allows us to carry out our mission. Whether volunteers are helping our accredited organizations or running our site visits, COA would not function without them.

This is why we like to pause every April to celebrate National Volunteer Month. Established in 1974 by Presidential Proclamation, National Volunteer Month aims to both celebrate volunteers and unite the nation in increased volunteerism throughout the month. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, over 62 million Americans volunteer at least one hour each year, with the average amount of time equaling to approximately 50 hours per person (that comes out to about 3.1 billion hours of donated time!). Previously we have acknowledged Volunteer Month by writing about starting a workplace volunteer initiative and had a guest post from one of our many wonderful volunteers. This year, we decided we wanted to get a bit more personal. How does COA staff connect with our own volunteer initiatives? What impact does it have on the communities we serve as well as our own? What can others learn from our story?

In 2012, COA staffers spent a day on Staten Island, cleaning out a home affected by Hurricane Sandy. The devastation was sobering. It helped us to realize that we were eager to give back outside of our day-to-day work. This led to the formation of an interdepartmental group to spearhead employee volunteer opportunities, now known as the COA Volunteer Committee. Since its creation, the committee has coordinated drives, off-site activities, and in-house events.

How we’ve volunteered

Activities

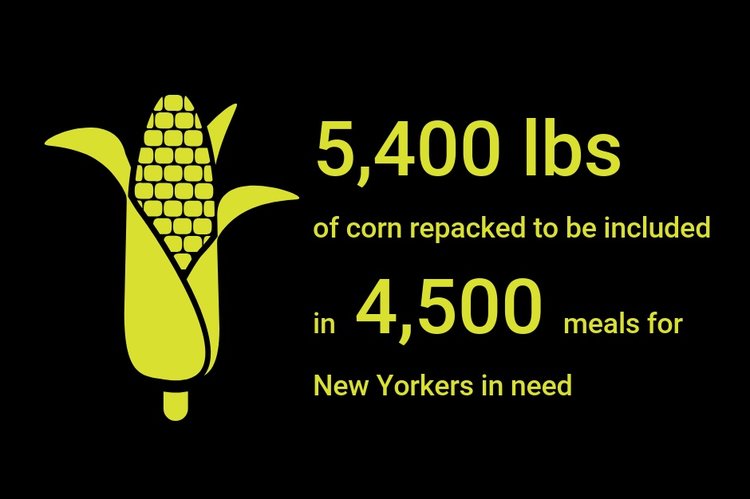

The committee kicked off its efforts in 2013 by participating in “Repack in Hunts Point” with Food Bank for New York City during National Hunger and Homelessness Awareness Week. We traveled to the Food Bank’s Food Distribution Warehouse in the Bronx and were tasked with sorting, weighing, and packing corn to be distributed to food pantries and community kitchens throughout the five boroughs.

Another one of our favorite activities was volunteering with the Pajama Program in 2015. The program provides new pajamas and books to children in need nationwide, many of whom live in group homes, shelters and temporary housing facilities. Volunteers had the opportunity to read to children from Pre-K and second grade classes, share snacks, and hand out pajamas and a book for each child.

We loved working with kids so much that later that year we volunteered with Association to Benefit Children (ABC). We took a field trip to Battery Urban Farm and volunteers worked with two classrooms of three- and four-year-olds. We ate pizza. We rode the subway. We gardened… After we were done, we all needed a nap!

In 2017, we volunteered with Coalition for the Homeless, helping wrap presents for children living in their network of shelters. The gifts were distributed to 140 kids at their annual Kids Holiday Party and to other children experiencing homelessness throughout the city. This one definitely put us in the holiday spirit!

We did a second event in Spring 2017 working with God’s Love We Deliver, helping to prepare meals for individuals and families living with serious illnesses. We learned about their mission, put our hair nets on, and packed soup to be distributed across their network. This partnership has continued with a few additional volunteer opportunities in 2018, as well as planned events for this year.

Another organization we’ve worked repeatedly with is The Friends of Governors Island. We’ve enjoyed helping them weed, rake, and maintain landscapes for this beautiful island we are lucky enough to work near. This work allowed us to give back in a way that is outside the scope of our day to day responsibilities and is vital to sustaining the public green space.

Drives

In addition to off-site opportunities, the COA Volunteer Committee has also organized in different types of drives to support the work of various human service organizations. These have included:

- Collecting coats from staff and others in our building to support one of the largest coat drives in the New York City area, hosted by New York Cares

- Collecting essential winter items (such as scarves, gloves, and hats) for youth in the Safe Haven for Children program as part of Lutheran Social Services of New York, Inc.

- Collecting toys for children at the Dr. Katharine Dodge Brownell School (operated by Rising Ground, Inc.)

- Participating in a canned food drive for City Harvest

- Participating in a gift card drive hosted by Sanctuary for Families, a community-based organization for survivors of intimate partner violence, sex trafficking, and related forms of gender violence

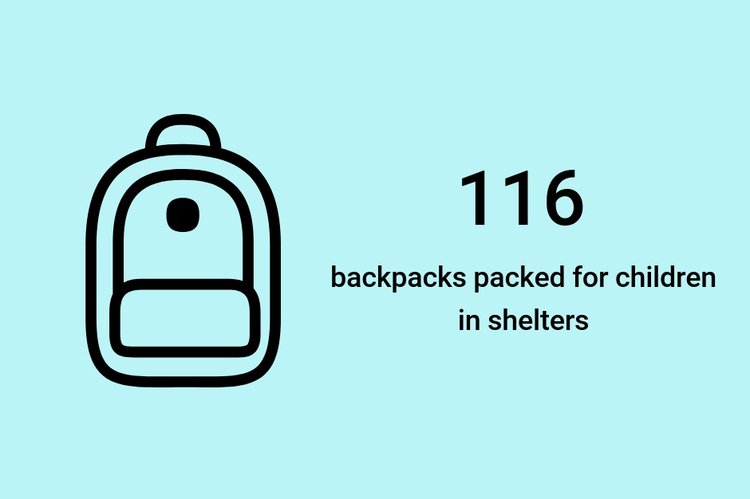

- Participating in Project Back to School with the Coalition for the Homeless, collecting grade-specific backpacks and school supplies for youth.

In addition, we have an evergreen drive: With so many COA staff traveling across the nation representing COA at various conferences and events, we’ve made an ongoing effort to collect hotel-size toiletries to drop off at a shelter for survivors of intimate partner violence.

Our impact

Since 2013, COA staff have volunteered over 400 hours through the COA Volunteer Committee alone! We’ve seen the impact both internally and in our community.

Volunteering as an organization can give staff a forum to team build and bond, engage with the community, and increase morale.

When we polled staff about what they like best about COA volunteer opportunities, promoting team-building and building camaraderie came out on top. Staff also appreciate that the activities connect back to our mission and provide a space for us to get to know one another outside of the office. Another thing that we enjoy about our volunteer efforts? They give us the warm fuzzies!

At COA, volunteering has offered everyone a chance to give back, reconnect with our mission, and to “step away from our screens for a day to do good and spend time together while doing so.”

What we’ve learned

What are the barriers to getting a volunteer effort off the ground? Our staff report conflicting appointments and time away from the office as the biggest hurdles. Finding the time to volunteer can be a challenge when you have a full plate. The activities themselves, the environment, or the level of physical activity required can be other factors that change the response from “Count me in!” to “Maybe next time…”.

In the effort to keep our mission as a committee going and overcome these barriers, we’ve picked up a few tips and tricks to make our events more successful and have the greatest impact.

Schedule smart

Consider the nature of the event, time of year and weather in you planning – i.e. don’t plan an outdoor event if it’s commonly snowy that time of year. Keep in mind whether staff are typically on vacation or stacked with meetings on certain days. By making these considerations early, you’ll be able to maximize the number of staff that are able to volunteer for your event.

Find the right fit

When choosing a volunteer event for your organization it’s important to assess if there is an activity or event that is a particularly good fit for your organization. For example, our toiletry drive fit well with our frequent staff travels. You may also want to consider current events and needs in your area, like we did in our response to Hurricane Sandy.

Engage leadership

A key component of planning a successful volunteer event is getting buy-in from leadership to get the necessary permissions and gain their support and involvement. Engaging leadership at COA has enabled to us receive donations on behalf of the organization. Depending on the event and how your organization wants to contribute (time, items, $$$, etc.), there are a few approaches you can use to utilize that donation to its fullest. For our last backpack and school supplies drive, we recognized that backpacks were the most expensive item we were asking staff to donate, so we used COA’s donation to purchase backpacks.

Promote convenience

If you’re planning a volunteer event that will require staff to make donations, it’s important to make it as convenient as possible for them. If the expectation is that staff will bring things in from home, highlight the convenience of being able to clean out and drop off at their workplace. If staff will most likely need to purchase items for donation, we highly recommended setting up a registry. It provides specific guidance and easy purchasing options for staff and allows the organizer the ability to manage the items donated.

Offer incentives

Though the joy of donating and contributing to a cause is often enough to get people involved, incentives can be a great way to engage folks and reward their participation. When soliciting staff to participate in an off-site volunteer event we highlight the opportunity for out-of-office time, an option to dress down, and even snacks or lunch. We’ve also conducted raffles alongside events, entering all participants in a chance to win a gift card. Be creative and know what will incentivize your audience.

Send out reminders

People forget. Particularly if it’s 7AM and you’re trying to get to work. Make sure to send frequent reminders!

BONUS Tip: Even with reminders, we highly recommend allowing for some buffer time for sign up and donation deadlines (i.e. tell people the deadline is a few days before you absolutely need the commitment or donation).

Encourage volunteerism

If your organization doesn’t have the capacity to plan a specific event, create an avenue for staff to learn about volunteer opportunities. We place information on a white board in our communal kitchen and have a Slack channel solely dedicated to volunteer information. This way staff can get the information and choose to participate on their own time if they wish.

Whether you’re planning an event for your organization or doing something on your own, we hope you will get out there and volunteer this National Volunteer Month!

Community demographics are continuing to evolve nationwide, making the need for culturally competent organizations more prevalent than ever. In this article, we will discuss what this means for you as a provider of social services, and how your organization can progress in this realm by exploring the what, why and how of cultural competence.

The what

First, let’s define cultural competence. It can loosely be defined as the ability to respect, engage, and understand individuals who have different cultural or belief systems, where the elements of culture include, but are not limited to: age, ethnicity, gender identity, gender expression, geographic location, language, political status, race, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, tribal affiliation, and religion.

The why

The term competency in regards to culturally responsive practice has been debated. Can one ever truly be culturally competent? There might not be a consensus, but as a provider of social services promoting cultural competence will enable you to better meet the needs of the individuals, children, and families you serve. Understanding your community and those you serve facilitates stronger partnerships, resulting in higher quality programs and service delivery. Research shows that organizational culture impacts its effectiveness. An organization that commits to cultural competence is not only better equipped to successfully address community service gaps and needs, but also creates an internal culture that fosters responsive and respectful interactions.

Here are just a few of the many benefits, it:

- fosters stakeholder engagement and empowerment

- ensures strategic initiatives, goals, and objectives to be culturally appropriate and inclusive of community needs

- supports the recruitment and retention of a diverse and inclusive governing body and workforce

- creates a safe and supportive environment that accepts and respects diversity

The how

Seek stakeholder feedback

Connect with your community! The best way to do that is to offer formal and informal ways for clients and community members to provide feedback about the work that you do. That’s why COA highlights the importance of stakeholder involvement in performance and quality improvement systems in its standards. As an organization, you get a sense of what’s working and what’s missing the mark. You can then tailor your services and outreach efforts to ensure that they are culturally appropriate. Most importantly, when you incorporate client and community feedback it makes those you serve active in organizational decision-making processes and promotes engagement and empowerment.

Conduct a community needs assessment

Conducting a community needs assessment is an effective way to identify strengths and resources in your community. It also highlights current gaps and service needs. Collaborating with community partners can enhance this assessment. You can also review other external needs assessments conducted by organizations with a community-wide focus. KIDS COUNT data center, a project of the Annie E. Casey Foundation, allows you to access local, state, and national level data and statistics on demographics and child and family well-being that can be incorporated into your assessment process.

Incorporate community demographics into your strategic planning process

Strategic initiatives should be responsive to changing community demographics and service needs. COA recommends that organization leadership review a demographic profile of their defined service population at least once every long-term planning cycle. However, it’s not enough to collect and review demographic data; it must inform an organization’s planning and operations. Promote cultural competence by establishing goals and objectives that are culturally appropriate for those you serve. Want to go a step further? Incorporate a cultural competency plan into your strategic planning process.

Foster a culturally responsive workforce

Promote cultural competence by having a diverse and inclusive workforce. A first step is ensuring that your human resources practices are culturally appropriate. Organizations should strategically recruit and employ personnel that reflect cultural characteristics of the service population. Is this a challenge for your organization? Create a plan that establishes goals for recruiting and employing individuals that represent your service population and community.

Another way you can commit to promoting cultural competence is by providing relevant education and training opportunities to personnel at all levels. Opportunities should not only focus on work with clients, but also address the internal workplace and interactions amongst other staff. Education and training should be tailored to the needs of your organization, but may include: language classes, interpreter training, mentoring programs, and diversity workshops. You can also conduct workforce assessments to inform ongoing personnel development opportunities to ensure that all staff is trained on culturally responsive policies, procedures, and practices. Once personnel have the necessary education and training, it’s time to integrate culturally responsive practices into everyday work with clients. As a provider, your goal should be to provide respectful, effective, and equitable care. This stems from adopting a service philosophy that is culturally responsive to those you serve, and culturally appropriate program-level policies and procedures.

Arguably one of the most important things that you can do as an organization is create safe and supportive environment where personnel can explore and gain an understanding of different cultures. You can do so by creating a cultural advisory committee to address workforce diversity issues or holding “cultural conversations” where staff can discuss diversity issues and learn from one another. Offering these types of forums reinforces a culture that is accepting and responsive to diversity.

Establish and maintain a diverse and inclusive board

One major responsibility of a nonprofit board is establishing and adopting organizational policy. Policies and procedures that support culturally responsive practice provide the framework for being a culturally competent organization. That is why having a board that reflects the demographics of the community it serves is so crucial. It’s no secret that board recruitment can be a challenge. If your organization is struggling to establish a board that is diverse and inclusive, establish a stakeholder advisory group that is representative of the community you serve and create a board recruitment plan that outlines strategies for getting everyone at the table. Need a little guidance? BoardSource is an excellent resource on board diversity, equity, and inclusion.

Are you feeling overwhelmed?

Don’t be. One of the most important things for organizations to keep in mind is that cultural competence is an evolving, active process; it’s not something that is attainable overnight. In fact, some researchers say there is a cultural competency continuum. The takeaway here is that every step you make towards becoming a culturally competent organization is a step in the right direction.

Want to learn more?

There are plenty of resources floating around the Internet that address cultural competence. Here are a few that you may find helpful:

The National CLAS Standards are a set of guidelines that aim to reduce health care disparities and advance health equity. COA developed a crosswalk to demonstrate how COA standards align with the National CLAS Standards and support the provision of culturally and linguistically responsive services.

National Center for Cultural Competency (NCCC)

The National Center for Cultural Competency (NCCC) aims to promote health and mental health equity through the promotion of culturally and linguistically competent service delivery systems and offers a variety of resources and publications geared towards the promotion of cultural competence.

Standards and Indicators for Cultural Competence in Social Work Practice

Are you a social worker? The National Association of Social Workers (NASW) developed standards and indicators for cultural competence in social work practice.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA)

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) provides a host of information around cultural competency in the field of behavioral health. Check out this manual which focuses on helping providers and administrators understand the role of culture in the delivery of mental health and substance use services.

Okay, your turn!

What are some challenges your organization faced in this area and how have you attempted to overcome them? Can you share any tips, tools or resources that lead to your success? Please leave a comment below and help others learn from your experiences.