I’m going to go out on a limb and say it: Mental Health is IN right now. Everyone from meme accounts to rappers is talking about it, and working on your emotional well-being no longer has the same taboo it once did. In fact, some might go so far as to say that your emotional health is intertwined with your physical health (and those of us in the human services field are probably nodding our heads vigorously at this one). Then it follows to reason that if both aspects of our health are equally important, they deserve equal insurance coverage. But is that what’s happening?

Like most things in the world of behavioral health, the answer is….kind of. In 1996, the Mental Health Parity Act was signed into law. It dictated that the annual or lifetime dollar limits in health insurance coverage be equal to medical and surgical benefits. Did this happen? Short answer, no. Long answer, insurers continued to lead policy and utilized the levers at their disposal to reduce costs and ultimately limit coverage. Employers and insurers began to put a larger emphasis on cost sharing, limits and caps on the number of visits with a care provider or number of days in a hospital were imposed, and benefits didn’t extend to substance use treatment. This led to the 2008 passage of the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (MHPEA), which gave advocates hope that further protections were being put in place to ensure equal coverage for behavioral healthcare. So now that it’s 2019, are we actually seeing parity?

MHPAEA 10+ years later

Reflecting on the decade-plus since its passage, what has the MHPEA done for health care coverage? The act has done several important things: it made sure that substance use treatment was included in the parity conversation, it protected mental health and substance use services from being subject to more restrictive cost-sharing and treatment requirements, it ensured equitable coverage for out-of-network treatment, and it gave patients the right to request information regarding medical necessity determinations and reasons for coverage denial. Despite these important steps forward in the battle for parity, implementation hasn’t been easy. Behavioral health providers are seeing 17-20% lower reimbursement rates than their medical counterparts, and the oversight varies wildly from state to state. Advocates such as Angela Kimball from the National Alliance for Mental Illness applaud the Federal law for paving the way for the removal of many of the traditional barriers to mental health treatment, but still feel “much more subtle discriminatory practices” remain an issue.

The “much more discriminatory practices” are what experts refer to as non-quantitative treatment limitations, which includes differences in how plans enact utilization management and define medical necessity, separate deductibles and co-pays for behavioral health services, limited options for in-network behavioral healthcare providers, and lower reimbursement rates. According to the Milliman Research Report on parity laws, this has resulted in decreased reimbursement rates for these provider’s services and approximately 32% of patients going out of network for treatment (in comparison to the 6% of patients that go out of network for their medical services).

Parity at the state level

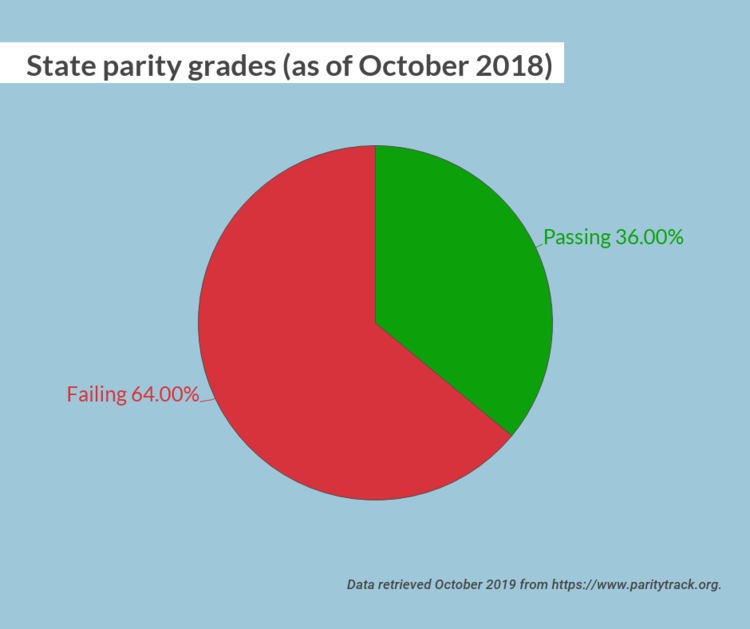

One major road block was inconsistent oversight and implementation at the state level. As recently as October 2018, 32 states received a failing parity grade. However, the state of Illinois was a star pupil, with a 100/100 grade. Illinois went above and beyond Federal parity policy by passing Public Act 99-480, which expands upon the MPHEA with provisions to extend coverage, provide education to the public about their rights, require minimum treatment benefits, and strengthen oversight and enforcement of the law. The Illinois statute extended applicability to plans not covered under the Federal parity law, such as fully insured plans for small employers and state and local governmental plans. It also extended the opioid antagonists covered in the plan. In addition, the legislation required the Illinois Department of Insurance to develop a plan for a consumer education campaign on mental health and addiction parity in order to help consumers, providers, and health plans better understand parity under the law. Finally, the law created an interagency workgroup and clarified the enforcement authority as the Department of Insurance. It’s this last piece, the interagency workgroup and clarification of enforcement, that promises continued success for Illinois parity. It promotes continual work, reflection, and analysis of Illinois’s parity statutes and clear delegation of responsibility.

The state of New York is an example of a state who has struggled with parity implementation but is actively trying to bolster its own Mental Health Parity laws. The Mental Health and Substance Use Disorder Parity Reporting Act was signed into law on December 22, 2018, and creates a reporting mechanism for health plan information to the Department of Finance to increase oversight of behavioral health management companies. The insurers will submit data to the department in order to keep track of potential non-qualitative treatment limitations. This is an important first step to identifying bad insurance coverage policy and protecting consumers.

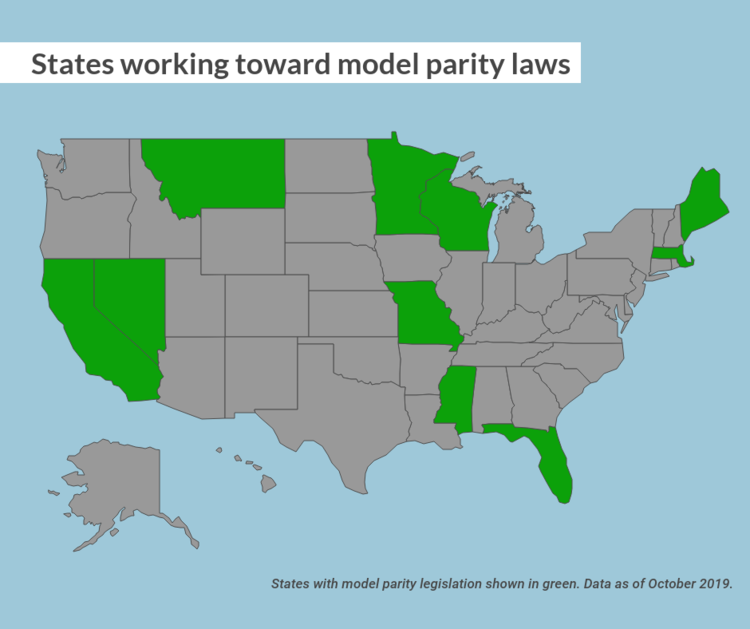

Illinois and New York aren’t the only states who are working towards true parity for behavioral health coverage. Pennsylvania has identified and fined a large insurance company and its subsidiaries for imposed behavioral health treatment, and Wyoming and New Jersey both recently enacted policy for insurers to meet MHPAEA requirements. While the United States might not be at a point where we can safely say we are full parity across the nation, states are taking the steps to get there.

What can I do about health parity?

Glad you asked! For starters, call your legislators! The following states have introduced model parity legislation; contact your state senators and representatives to let them know you want them to support health parity: California, Florida, Maine, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, and Nevada.

Don’t see your state here? The American Psychiatric Association has you covered with model parity laws for every state!

At the Federal level, there are several bills that could use your support. Contact your senator or house representative and let them know you support the following bills:

- The Mental Health Parity Compliance Act (S. 1737/H.R. 3165)—This would require comparative analyses about the design and application of managed care practices. That information would then be collected by federal agencies, who would analyze the plans’ compliance, specify what must be done to bring it into compliance, and submit an annual report of their findings.

- Parity Enforcement Act (H.R. 2848)—This bill authorizes the Department of Labor to issue monetary penalties for those violating the federal health parity law.

Reach out to your senators and representatives! Make sure that your state is providing you the best behavioral health coverage possible. Your mental health is just as important as your physical health, and it should be covered. The MHPAEA was an important step in the fight for parity, but we are a decade out from its passage and have learned lessons about the act’s limitations. We should be using those learnings to get us closer to full parity.

Since Congress passed the Family First Prevention Services Act (FFPSA) in February 2018, stakeholders across the U.S. have been working to maximize the opportunity posed by this tremendous reform to our child welfare system. To ensure that children and families reap the positive benefits of FFPSA, service-providing agencies, social workers, child welfare officials, accrediting bodies, policy makers, and advocacy organizations have been rigorously planning for implementation, all while trying to keep up-to-date on the latest guidance and policy.

Looking for an FFPSA 101? Watch our informational video.

As COA began working with service providers impacted by FFPSA, we found that organizations were not only interested in information about the accreditation process, but also resources relevant to the larger scope of FFPSA provisions. That’s why we created the COA FFPSA Resource Center, a hub of FFPSA-related content including federal guidance, tools and resources, accreditation information, events and trainings, and news.

We are continually evolving the website as new guidance and/or policy is released and as states move forward with implementation. Have a resource, article, or tool that you’d like to see posted on the Resource Center? We’d love to hear from you! Reach out to us by email at PublicPolicy@coanet.org.

Just starting to peruse the site and not sure where to start? Fear not! We’ve created a list of 5 helpful resources to get you started.

1. Federal Requirement Comparison: QRTP and PRTF

From the Building Bridges Initiative

With the support of the Annie E. Casey Foundation, Building Bridges created this comparison to assist providers in understanding the federal requirements set forth for Qualified Residential Treatment Programs (QRTP) and Psychiatric Residential Treatment Facilities (PRTF). The information is organized in a table by requirement component, so that readers can do a line-by-line comparison of each program’s respective requirements. Though QRTPs and PRTFs have some similarities, these programs were created and defined separately in federal law in order to establish varying levels of care for children and youth with significant behavioral health needs.

Building Bridges is a national initiative working to identify and promote practices and policies that will create strong coordinated partnerships and collaborations between families, youth, community- and residentially-based treatment and service providers, advocates, and policy makers to ensure that comprehensive mental health services and supports are available to improve the lives of young people and their families.

2. Responsibly Defining Candidacy within the Context of FFPSA: 5 Principles to Consider

From the Center for the Study of Social Policy

The Center for the Study of Social Policy created this brief of guiding principles for states to consider as they work to identify a definition of foster care candidacy that fits within the context of their state policies and prevention service array.

FFPSA defines the term ‘child who is a candidate of foster care’ to mean “a child who is identified in a prevention plan under section 471(e)(4)(A) as being at imminent risk of entering foster care…but who can remain safely in the child’s home or in kinship placement as long as services of programs specified in section 471(e)(1) that are necessary to prevent the entry of the child into foster care are provided” (Sec. 50711). This means each state will be responsible for defining candidacy in their State IV-E Plan, which will be submitted to the Children’s Bureau. State definitions of “candidacy” will be extremely important in deciding which children and families will be served under FFPSA prevention services. This resource provides a guiding methodology for state policymakers in creating that definition and assists in considering the way such a policy will impact children and families in their state.

3. Program Standards for Treatment Family Care

From the Family Focused Treatment Association (FFTA)

As we learn more about the impact that FFPSA implementation will have, it has become clear that there is a need to bolster the continuum of child welfare services offered to meet the needs of children and families. Treatment Family Care (TFC), also known as Treatment Foster Care (TFC), has emerged as a leading service to meet the behavioral needs of children in home-settings rather than residential care. The strict parameters established around residential placement under FFPSA puts a spotlight on TFC as a service that can maintain a residential level of care while keeping children and youth in a home-setting.

Though TFC services are provided across the country, federal guidance related to funding opportunities, practice standards, and program oversight has never been issued. Fortunately, Congress is currently considering the Treatment Family Care Services Act (HR3649 and S1880), which will provide states with a clear definition and guidance on federal TFC standards under the Medicaid program and other federal funding streams. This clarification will promote accountability for states offering TFC, support FFPSA implementation, promote appropriate TFC services for reimbursement, and drive personnel training and standards.

FFTA first published their own Program Standards for TFC in 1991 to define the model and set parameters for the field. In 2019, FFTA published the revised 5th edition, which provides several updates to the previous edition and in particular approaches the standards from a broader perspective of Treatment Family Care. This is in response to the changing needs of children, youth, and families; programmatic changes; and service expansions impacting TFC services. In particular, the new edition expands the view of TFC by integrating a focus on children living with kin. This inclusion was necessitated by an increasing expectation to meet the treatment needs of children in kin settings, stemmed by the belief that living with family can minimize the trauma associated with separation from parents.

View the FFTA’s program standards here.

4. Title IV-E Prevention Services Clearinghouse website

From the U.S. Administration for Children and Families (ACF)

The Title IV- E Prevention Services Clearinghouse was established in accordance with FFPSA by the Administration for Children and Families (ACF) within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Its goal is to conduct an objective, rigorous, and transparent review of research on programs and services intended to support children and families and prevent foster care placements. Programs submitted to the Clearinghouse are rated as “well-supported”, “supported”, “promising practice”, or as “not meeting criteria”. The initial programs that have been rated include mental health services, substance abuse prevention and treatment services, in-home parent skill-based programs, and kinship navigator programs.

Ratings will help determine programs’ eligibility for reimbursement through Title IV-E funding. The Clearinghouse continues to be updated as new services are reviewed and rated, those interested in receiving real time notifications of updates can sign up here.

Access the Title IV-E Prevention Services Clearinghouse here.

5. National and state FFPSA news

From our FFPSA Resource Center

Implementation of FFPSA will mark the largest reform to our national child welfare system in decades. Since FFPSA passed in February 2018, there have been hundreds of news outlets reporting on the many components of reform at the national and state level, including information on implementation, related legislation, funding opportunities, service delivery, and more. The large scope of provisions can make it difficult to find the information that is relevant to your role in implementing FFPSA. That’s why COA created a FFPSA news round-up, updated regularly with content published related to state-specific activities and national news related to FFPSA.

State-level news can be viewed here and national-level news can be found here. Want to get alerts when important updates are published? Sign up for our mailing list.

We hope these resources will support you and your agency in learning more about the provisions of FFPSA. We would like to thank all of the organizations that have produced content to assist our field with this important legislation.

Though we’ve identified these five resources to get you started, we encourage you to continue your research and explore all of the information available at www.coafamilyfirst.org. And since we couldn’t pick just five…

Bonus resource!

Accreditor Comparison Guide

Needing to pursue national accreditation as a result of FFPSA? The first step is to find an accreditor that is the right fit for your organization. To support agencies in choosing an accreditor, we created a comparison guide that details the differences between the COA, CARF, and JC accreditation processes.