Community

Going Beyond the Opioid Crisis: Deaths of Despair

If you were to open a newspaper and select an article at random, chances are you would hit a piece on the American opioid crisis. Whether the news is about a pharmaceutical company being taken to court, a Democratic presidential nominee hopeful’s plan to address the climbing overdose rates, or a report on the effectiveness of Heroin Assisted Therapy, opioid news is everywhere. Does all this attention mean we can expect the crisis to abate?

Most likely not. Projections of opioid fatal overdose rates predict a sharp rise in the coming years, with an optimistic peak in 2022 before leveling off. Dr. Donald Burke, a researcher into the American Drug Epidemic, points to the increasing percentage of individuals who first use after exposure to prescriptions and continue to misuse despite the government’s tightening of regulations as evidence for the continual steady rise. He cautions that “the US has experienced four decades of exponentially increasing overdose deaths, so stabilization in the next 2 to 7 years may be more of a hope than a scientific reality.” One of the reasons for this may be that our current approach to targeting the opioid crisis is like targeting the stems of a weed—no matter how much we cut off, if we don’t address the roots, the weed will just keep coming back.

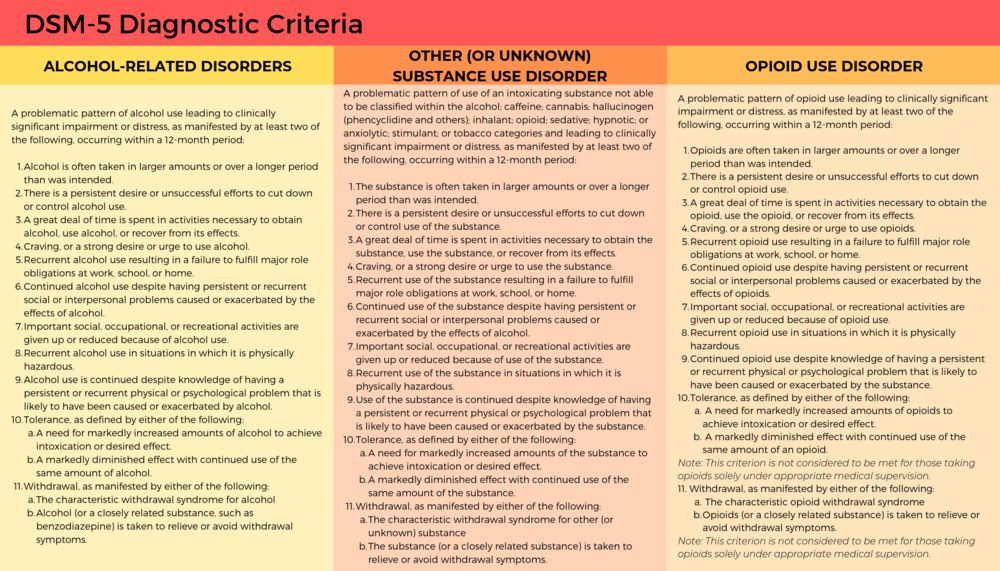

It may be myopic to treat the opioid epidemic as a unique factor in the decreasing American life expectancy. If you look up “Other (or Unknown) Substance Use Disorder” in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5) and compare it to opioid use disorders or any other substance use disorder, you will notice the same defining features. So what makes opioids unique? It could be that opioids’ special status comes more from the attention being put on it rather than the drug itself. In the past decade, researchers have found an increase with what they refer to as “deaths of despair”: an overall rise in deaths related to alcohol, illicit drugs in general, and suicide. To address the opioid crisis, we need to look at it in context of these “deaths of despair” and explore its underlying causes.

Substance abuse on the rise

Opioids are not the only drugs that have been on the rise in the last decade. From 2008 to 2013, amphetamine-related hospitalizations increased 245%, and some states have seen the overdose rates surpass those of opioids. Texas is not only seeing a rise in meth use, but also seeing a related increase in rates of life threatening infections, such as HIV and MRSA. In 2015, the state of Wisconsin estimated that meth cost them $424 million, including both the cost of health care and lost productivity. Even opioid overdoses are often not just from opioids: 30% also involve benzodiazepines.

Illicit drugs are not the only culprits when it comes to drastic rises in substance abuse. Between 2002 to 2013, problem drinking rose to the level of a public health crisis, especially among minorities and women, and to unprecedented levels in older adults. According to the CDC, in 2018 over 25% of high school students used a tobacco product in the past 30 days. Beyond the Juul fad that we commonly associate with youth, we have seen a rapid growth of e-cigarette use in adults, with 1/3 of current adult e-cigarette users being those that consider themselves “nonsmokers.”

When you start to look at the numbers it becomes clear: We don’t just have an opioid problem. We have an overall substance abuse problem. This doesn’t even factor in some of the other consumption related disorder (eating, gambling, screen addiction, etc.). Looking at these unhealthy relationships with external stimuli, you can’t help but wonder: What is happening in America to make matters so desperate?

Deaths of despair

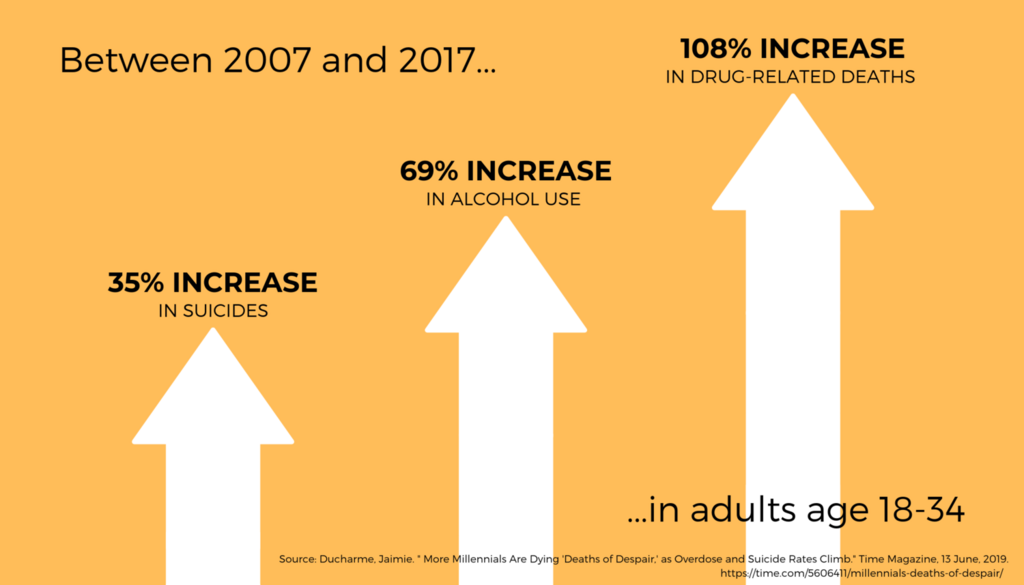

“Deaths of Despair” may sound like a line from an Edgar Allen Poe poem or a new Taking Back Sunday album, but it’s what’s at fault for decline in the average age of American life expectancy. Deaths of despair are commonly agreed upon as those involving drugs, alcohol, or suicide—deaths related to pain, distress, and social dysfunction. Adults between the ages of 18 to 34 have been hit particularly hard–in 2017, 36,000 died from a “death of despair.” For adults between the ages of 45 to 54, the mortality rate rose by a half percent each year from 1993 to 2013. While not as dramatic, that increase has accounted for an alarming decreased life expectancy. If you look at this time period from a societal standpoint, there are a few things that pop out: the Great Recession, the rise of social media, and a rise in loneliness.

While the Great Recession can’t account in its entirety for the current public health crisis, it has played a role. For every 1% increase of unemployment rates, there is a 3.6% increase in opioid-related deaths and 7% increase in emergency room visits, as well as an increased use of tobacco, problem drinking, and other illicit drugs. A comparison of data today versus data from of adults in the mid-1990s and early 2010s shows there have been significant increases of mental and emotional distress, especially among individuals with a lower socioeconomic status.

With increasing rates in social media use, we have begun to see a positive correlation in increasing rates of loneliness. Loneliness has been shown to be positively correlated with suicidal ideation and parasuicide behavior, and a study on young U.S. adults (between ages 19 and 32) found that those with high social media use (around 2+ hours per day) were more than three times as likely to have perceived social isolation, one way that social scientists operationalize loneliness. Studies have shown that conversely, limiting social media use to 30 minutes per day leads to significant improvement in well-being, showing a causal link between the two. Dr. Oscar Ybarra, a professor of psychology at the University of Michigan, theorizes that social media activates social comparisons in users, leading to feelings of inadequacy. While social media can be used effectively as a community builder, it is hard to ignore the relationship between the increased use of social media and the increase of factors that can lead to suicidal thoughts and behaviors, another form of the deaths of despair.

In addition to these factors that cause distress, there has been an increasing sense of loss of community, a protective factor known to mitigate these negative stressors. In his new book, Tribe: On Homecoming and Belonging, Sebastian Junger argues that on our path to modernity, America has paid with the currency of belonging. Much of modernity has been about perfecting the lack of need for others. As people feel increasingly like they can’t measure up to others and have a lower sense of belonging, we’re creating the perfect storm for alienation and depression.

Thinking of substance abuse as a biopsychosocial disorder highlights the relationship between trends in American society and our decreasing life expectancy. This in turn highlights how hard it’s going to be to tackle the opioid epidemic– there’s not going to be one easy solution. The tech sector has responsibility to create community instead of disrupting it, regulators have a responsibility to pass legislation to help get people the necessary supports they need, and we have a responsibility to each other. The opioid epidemic isn’t going to go away any time soon, but we certainly can’t speed up its departure by continuing to ignore the root of the problem.