The most vulnerable members of society have also been the hardest hit by the ramifications of the COVID-19 pandemic. The work of nonprofit organizations serving those populations continued largely uninterrupted over the past several months—despite sparse protective gear for staff, thinly-stretched funds, and minimal to no national guidance about how to safely proceed.

Behavioral health centers, foster care services, homeless and women’s shelters, and many other human and social services organizations have not shut down. They have been navigating urgent and rapidly changing issues on the fly to keep their essential staff safe as they deliver critical services.

The Council on Accreditation (COA) discussed the changes and challenges of recent months with eight of our Sponsoring Organizations, which are nonprofit membership bodies comprised of organizations that provide human and social services (many of whom are accredited by COA). Sponsoring Organizations serve as critical advisors to the COA, helping us understand the accreditation needs of provider agencies, industry trends, and environmental challenges within the human and social service landscape. Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, they have played a central role in helping their member agencies figure out how to safely continue operating in unfamiliar terrain.

We wanted to take a moment to recognize their work and highlight the innovation and creativity that emerged during this difficult time. Their stories illustrate best practices in “continuous evolution” and “resilience” that help organizations push through difficult times.

Shifting priorities

High levels of uncertainty have been a constant since March. Every organization has had to re-evaluate priorities and re-direct resources accordingly.

“One of the biggest lessons we’ve learned from the past few months is the concept of truly listening to members. Never has that been more critical,” said Mohini Venkatesh, Vice President of Business Strategy at the National Council for Behavioral Health (National Council). “We had to figure out how to represent the full continuum of experience of our members —from those serving wealthy communities to the underserved—in an environment where everyone’s experience was highly variant and changing fast.”

High-frequency membership surveys and town hall meetings facilitated by the CEO of National Council helped them keep the biggest challenges facing members front and center. Members’ inability to access to personal protective equipment (PPE) surfaced as a high priority early on. A survey of its members found that nearly 83% of behavioral health organizations did not have enough PPE for two months of operations.

When National Council put out a mass call to its members about PPE, it received requests for roughly 2 million masks within 48 hours. Although completely outside of its normal focus, National Council moved quickly to find a manufacturer and contractor that could fulfill and distribute its’ members PPE order.

The Network of Jewish Human Service Agencies (NJHSA) also went into action to provide PPE for its members after hearing safety concerns from agencies that interact with high-risk senior populations and hospice patients. It collaborated with several other organizations to do a group bulk purchase of PPE.

Catholic Charities USA (CCUSA)who serves millions of people per year, has distributed $6.1 million to agencies for COVID-19-related disaster grants and helped providing PPE, delivering almost 2 million face masks, 650 gallons of hand sanitizer, and gloves, masks, shields, and gowns. Across their network of facilities, they have seen a 50%-70% increase in clients seeking assistance including a broader demographic than low-income and poor households that traditionally walk through their doors including an increase in middle-class families who lost their jobs as the pandemic surged.

Rapid coalition-building

Collaboration was also central to the work of the National Foundation for Credit Counseling (NFCC), a nonprofit financial counseling organization, as states started to lockdown. With many Americans facing sudden unemployment or a dramatic reduction in work hours, financial stresses were running high – people needed short-term relief from paying credit card bills, mortgages, and other debts.

NFCC recognized that consumers needed an immediate short-term solution, regardless of where they sought counseling. They took a lead role in collaborating with other nonprofit credit counseling agencies, credit card issuers, lenders, and regulators to develop a national emergency payment relief program. The program allowed consumers to skip payments without penalties or damage to their credit rating.

“We experienced five years-worth of progress in a period of five weeks,” said Bruce McClary, Vice President of Marketing for NFCC. “It would have been an impossible goal to achieve if we had not already built strong relationships with key industry stakeholders and developed a solid communication framework.”

Facilitating communication and problem-solving

One of the top priorities for nearly every organization we interviewed was facilitating communications between its members to problem-solve.

The Alliance for Strong Families and Communities (Alliance), which is comprised of a variety of nonprofit human services organizations and state associations, initiated regular pulse surveys to assess members’ most immediate needs. The lack of guidance about how to deal with rapidly changing COVID-19 developments was a major stress point.

“Being nimble and taking risks with our communication strategies was crucial,” said Lenore Schell, Senior Vice President of Strategic Business Innovation at the Alliance. “Our guiding principal was to act as the facilitators, not the experts. We launched webinars in the early stages of the pandemic knowing we had few answers to provide, but it created an environment of trust for dialogue with and between members.”

The Association of Children’s Residential Centers (ACRC) also positioned itself as a communications hub for its members, which are residential centers for children. They couldn’t close down services and had to quickly figure out how to keep residents and staff safe in a setting where it is nearly impossible to social distance.

“Meeting the needs of behaviorally challenged young people is already tough work. And the COVID-19 pandemic created additional complexity at every level,” said Kari Sisson, Executive Director of the ACRC. “We quickly realized that the field needed a way to safely exchange information to develop policies, procedures, and best practices – and learn from others’ experiences.”

Affinity groups that were created before the pandemic served as a critical information-exchange for members. An affinity group that served kids with autism and severe brain injuries was able to learn a great deal from an agency in Massachusetts that was hit hard by COVID-19 – it helped peers think through how to plan for adjustments to family visit polices, establishing isolation units, and other safety issues.

Providing opportunities for peer collaboration became an immediate focal point for the Child Welfare League of America as well; it is comprised of agencies that serve vulnerable children and families. In the early stages of the pandemic, they gathered a small group of agencies from the hardest-hit states including New York and Washington to discuss challenges and lessons learned. CWLA also initiated “open mic” weekly conversations to let all member agencies voice their struggles and exchange information about what was working.

“We became a funnel for information for the industry, helping members navigate how to put new policies and protocols into place,” said Julie Collins, Vice President of Practice Excellence for CWLA. “We are still receiving daily inquiries from agencies about how others are dealing with specific issues.”

CWLA shared the intelligence from its various forums with its entire network of members via webinars and best practice newsletters. Topics spanned a wide range of issues from helping foster parents manage e-learning to guidance on recruiting and training staff virtually to establishing protocols for an employee that tests positive for COVID-19. They also arranged for Congressional representatives to hear directly from small agencies about their concerns.

Advocating change

As the COVID-19 lockdown hit different parts of the U.S., health and human service agencies had to abruptly transition as much as possible to virtual mode, often with little warning. Telehealth services suddenly became the norm instead of the exception.

“Initially, the government and insurance providers were only allowing telehealth services that used both video and audio capabilities. We had to help our agencies fight for allowing telephone-only services,” said Reuben Rotman, CEO and President of Network of Jewish Human Service Agencies (NJHSA). “There are big segments of the population that don’t have access to a computer or the internet, or they simply don’t know how to use it.”

For example, one of the agencies under NJHSA was working with a patient suffering from agoraphobia who had not left her house for nearly a year. Her therapist was able to counsel her via Zoom sessions – a more relaxing environment for the patient – and actively workshop steps that reduced her anxiety about getting into her car.

Although shifting to telehealth so quickly presented numerous challenges, it is also brought to light the effectiveness of alternative approaches.

“Telehealth is helping agencies live the true value of person-centered care – delivering treatment remotely to those who prefer that option,” said Venkatesh of National Council. “While many questions linger, the rapid deregulation of telehealth opened the flood gates. It’s clear that virtual services have great value, and we’ll need to help regulators understand the need for a hybrid model moving forward.”

Nancy Ronquillo, CEO of Children’s Home Society of America, the oldest network of child-welfare agencies in the U.S., said that their members expressed similar sentiments about shifting to virtual visits and counseling with families. “For some families, doing a 15-minute phone call a few times per week instead of a one-hour home visit with an agency worked much better,” said Ronquillo. “When agencies were freed from their traditional boundaries, it helped them test and realize how alternative strategies can work better for some kids and families.”

Acting quickly

Health and human service agencies were overwhelmed with the logistics of managing day-to-day operations, leaving little room for them to process new developments. Many of the organizations we interviewed took on this “processing” role, serving as a source of clarity on fast-moving critical issues.

When the U.S. Small Business Administration announced details about the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) loans, Children’s Home Society of America provided immediate guidance to its members so they could quickly plug into the application process. They also facilitated one-on-one calls between CEOs of its member agencies to troubleshoot the nuts and bolts of working with banks on the loans.

At (CCUSA), they have continued to push throughout the pandemic for the availability of stimulus funds and increased funding for programs like the Emergency Food and Shelter Program to support the most vulnerable of populations.

The Alliance sent communications about PPP almost daily, highlighting key details about eligibility, deadlines, and how the process worked. Many of the Alliance’s members said that without those communications, they would have missed out on the PPP loans.

Looking ahead

Uncertainty continues to linger for the foreseeable future. Short-term changes are putting long-running challenges into sharp focus, giving nonprofit organizations a chance to think more creatively about how they deliver value to those they serve. We are inspired by the spirit of collaboration and resilience within the nonprofit world to continue to serve while tackling unforeseen challenges.

COA’s President and CEO, Jody Levison-Johnson recognizes that COVID-19 has been and will continue to be a game changing experience. “COA is continuing to evolve to ensure that our standards and processes provide the greatest impact on the people and communities served by human and social service organizations. We thank the entire COA community for all of the work being done during these challenging times to ensure the continuity and quality of service delivery to the most vulnerable of populations.”

If we can be of any assistance, please let us know how we can help.

When it comes to serving communities and responding to individuals in crisis, law enforcement agencies and human service systems each play a role in maintaining the safety and stability of their communities. Substance use, child welfare, intimate partner violence, suicide, juvenile justice, mass violence — these are not only some of the most prominent societal challenges we face today, but also circumstances where both police officers and human service professionals are on the front lines.

The roles of law enforcement and human service agencies therefore consistently overlap. In communities and environments where needs are intensified and resources limited, this overlap comes into sharper focus. When behavioral healthcare is inaccessible, or social service systems are overburdened, communities often turn to law enforcement to fill in the gaps — sometimes leading to serious negative outcomes that can inflict trauma, injury, or death:

- Foster youth arrested and handcuffed for running away

- Mental illness played a role in 25% of fatal police shootings in 2017

- Misunderstanding disability leads to police violence

Such incidents are not only harmful to the individuals involved, but can also irrevocably damage a community’s trust in its police force and social support systems. These trends are a clear indicator that communication and partnerships between law enforcement agencies and human service providers need to be examined and strengthened.

Collaborative approaches to crisis intervention

The relationship between behavioral health and policing cannot be overstated; according to the National Alliance on Mental Illness, individuals in mental health crisis are far more likely to be confronted by police than to receive medical attention. More than 90% of patrol officers encounter individuals in crisis, with an average of 6 encounters per officer per month, but officers are often unprepared to meet the unique challenges of de-escalating a person with a disability or mental illness in crisis. A traditional law enforcement approach — “command and control,” — designed for crime intervention is likely to elicit fear and disorientation in individuals with disabilities or who are in emotional distress. Such approaches pose a significant risk of triggering a trauma response and escalating the dangerous behavior, increasing the likelihood for excessive force to be deployed.

In response to these challenges, law enforcement agencies have increasingly recognized the value of diversifying capacity and expanding officers’ skill sets in order to increase safety and efficacy in crisis response. In addition to ramping up efforts to educate officers on trauma, mental illness, and disability, and expanding training on de-escalation and crisis intervention techniques, many departments are adopting innovative new models to partner with behavioral health and human service professionals in police work.

Crisis Intervention Teams are one popular model in use in 2,700 communities across the country. The core components include recruiting, selecting, and training officers to serve as designated responders to mental health crises, and establishing relationships with a designated mental health receiving facility and other resources in the community to facilitate immediate emergency entry into the mental health system and reduce barriers to care. Officers receive 40 hours of intensive training on common disorders, developmental disability, and crisis de-escalation skills. Key to the success of this model are: ensuring adequate staffing to maintain continuous CIT coverage, equipping emergency dispatchers with the skills needed to identify when a CIT response is appropriate, and designing and delivering training curricula with the collective input of law enforcement, behavioral health specialists, and advocates. Evaluation of the CIT model indicates that it yields positive results, reducing officer injuries as well as the need for more intensive and costly law enforcement responses as well as increased referrals to emergency health care and accessibility of mental health services.

Co-responder programs are another partnership strategy with growing interest. Los Angeles, Omaha, Mesa, Arizona, and Huntington, West Virginia are among the jurisdictions that are adopting or expanding programs in 2019 to embed therapists, social workers, or addiction counselors into police departments. There is no standardized model, and program scope varies widely from place to place: some departments hire behavioral health specialists directly while others coordinate part-time or rotating coverage from a local provider; some target suicide and others substance use; they may be first on the scene or “secondary responders”; responsibilities can range from emergency response, community patrol, or even follow-up and case management. Although the programs are incredibly diverse, the rapid rate of adoption points to a culture shift in law enforcement: an emerging understanding of the agency’s role in responding to complex issues facing their communities, willingness and recognition of the value of working closely with human service professionals, and an investment towards diverting individuals in crisis away from the criminal justice system.

Establishing boundaries

Responding to individuals in crisis in the community is not the only circumstance where law enforcement and human services intersect. Although the integration of social workers and therapists into the world of community policing is a growing trend, for many human service providers — especially resource-starved ones — engaging police departments for assistance is standard operating procedure that may come with unintended consequences.

In a May 2019 lawsuit filed against the Administration for Children’s Services, the New York state appellate court ruled that family courts do not have the authority to issue warrants for foster youth who have run away from their placements — a longstanding practice. In 2017, the child welfare agency was granted 69 arrest warrants for children in their care; that was after guidelines for seeking warrants were tightened in 2015, when the number of arrest warrants issued was up to 125. In a majority of these cases, police officers deployed to retrieve missing youth end up putting them in handcuffs and in jail cells, regardless of safety risk.

Runaway behavior in foster care can often be attributed to trauma — children leave their foster care placements to be with the family members from whom they’ve been separated or other loved ones, or due to conflict with their foster parents. Being apprehended and even restrained by police officers and forcibly returned to settings where they may not feel safe exponentially compounds that trauma. The already fragile (or absent) trust in the child welfare agency may be eroded, often irrevocably, and the agency’s motivation may be perceived as punitive vs. protective.

In congregate care, the intensive needs and challenging behaviors of residents can often overwhelm the capacity of personnel and for many residential facilities, a common response to harmful or disruptive behavior, or unauthorized leave, is to summon police officers. In some communities, police departments report responding to struggling facilities multiple times a day. As with crises that take place in the community, the consequences of calling the police can be significant if the appropriate skills and protocols are not in place. And for organizations, chronic reliance on police intervention poses additional risks: therapeutic setbacks to service recipients involved, damaged staff morale, and diminished perception in the eyes of the host community and collaborating providers.

In 2015, California passed legislation aimed at reducing the frequency of law enforcement intervention in group homes and other residential facilities for children and youth. But policy or regulation is unlikely to be effective if the underlying causes are sidestepped. Experts argue that frequent calls to law enforcement are an indicator of deeper issues: inadequate staffing, insufficient training, ineffective programming, or a need to reassess admission/screening criteria. The continuum of challenges endemic to social services — underfunding, understaffing, burnout, turnover — hamper providers’ ability to meet the needs of their service population and maintain a safe and stable therapeutic environment.

If police intervention is unavoidable, then effective collaboration and proper training is critical. Providers and police departments must ensure that responding officers are familiar with the characteristics and needs of the service population and learn the skills necessary to safely de-escalate, retrieve, restrain a service recipient utilizing the least restrictive response to maintain safety. Recommendations from advocates include:

- Jointly evaluating policies and protocols to emergency response

- Creating Memoranda of Understanding between police departments and providers to better define roles and expectations around interventions, and ensure that responding officers are given relevant details about the residents in crisis

- Better data collection and analysis on the frequency and nature of law enforcement intervention in treatment settings

Children’s Village, a COA-accredited provider in New York, has called upon city leaders to form a Runaway Youth Taskforce to bring together law enforcement and social services in developing a new model for preventing and responding to runaway youth.

Meeting the mental health needs of police officers

A recent cluster of officer deaths by suicide has shed a harsh light on the challenges of addressing the mental health needs of the law enforcement community. Officers are at increased risk of PTSD, depression, anxiety, substance use, and suicide due to constant threat of violence or actual violence and exposure to death and trauma, in addition to chronic work stressors such as sleep deprivation and fatigue. Although repeatedly acknowledged by law enforcement agencies and police union leadership, the mental wellness needs of police officers are still persistently unaddressed. The culture of law enforcement has often been cited as a major barrier to care, with officers reporting fear of perception of weakness, alienation from fellow officers, and other potential professional repercussions as a result of seeking out needed services and supports.

Ignoring the mental health of police officers puts communities at risk. Studies have linked PTSD with impaired decision making ability — a critical implication for police officers in potentially life-threatening situations, and the potential for excessive or deadly force. These incidents not only increase the risk of injury or fatality of those involved, but also negatively impact the relationship between the community and law enforcement.

The human services field may be uniquely positioned to make a positive impact in this area. Professional staff in the social services and behavioral health field share many of the same work stressors as police officers — excessive caseloads, exposure to traumatic events, vulnerability in the community or service environment — and the impact of secondary or vicarious trauma has become a prominent area of research and advocacy in the human services field. Providers can bring significant knowledge to the table for law enforcement agencies about identifying and mitigating the effects of PTSD and secondary trauma, appropriate resources for treatment and support, and strategies for bolstering officers’ resilience.

Increasing the presence of behavioral health professionals in law enforcement settings can provide multiple benefits — not only by distributing or diverting the “social work” attributes of community policing, but also by providing an avenue for officers to seek support and referral to available services. Law enforcement leaders might also consider whether services provided outside of the auspices of the law enforcement agency might be more accessible to officers, potentially reinforcing confidentiality of services and softening the impact of stigma. Service providers can also assess opportunities to expand or tailor their service array in a way that focuses on the unmet needs of this population or supports their families. Research suggests that cultural competency — awareness of and responsiveness to the cultural and professional idiosyncrasies of police work — is pivotal to the accessibility and efficacy of psychological interventions targeted at police officers, and may be enhanced through peer-driven program design.

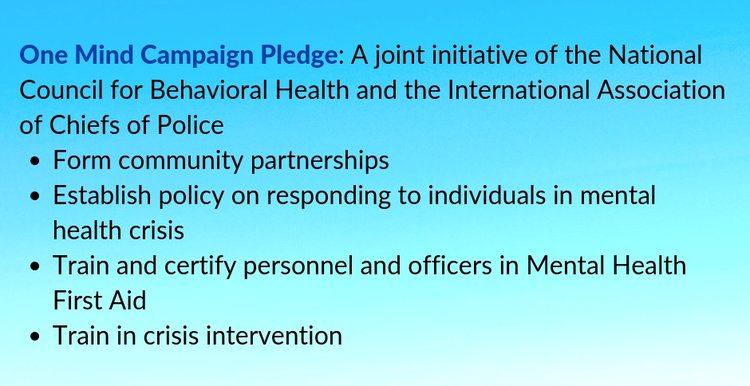

To protect and serve — and partner

Communities today are recognizing that the most pervasive social and public health challenges they are confronted with cannot be overcome without constructive collaboration between the social service, behavioral health, and criminal justice systems. Successful collaboration hinges, however, on meaningful assessment of areas of strength and need, clearly delineated roles and responsibilities, and a shared commitment to invest in the most effective solutions. Many agencies are developing or pursuing creative strategies to build partnerships between providers and police officers, with the understanding that joining forces is imperative to forming a greater understanding and capacity to meet the needs of their shared community, strengthening public trust and improving outcomes across all systems.

We’d love to hear from any organizations with experience in human services – law enforcement collaboration. Please share any promising practices or lessons learned in the comments below.