By Amy Templeman, director of Within Our Reach at Social Current

There is a shift taking place across the nation regarding child abuse and neglect fatalities. These tragedies, long considered inevitable, make headlines across every community and jurisdiction, with a focus on why systems failed our children and how these children fell through the cracks.

One finding points to the fact that child welfare systems have historically been focused on addressing harm only after it has occurred. Now imagine a system that works collaboratively across multiple agencies to provide the resources and supports that families need to prevent abuse and neglect before it can occur. That is the shift taking place today, with demonstration projects taking place across the United States, including Indiana, that are identifying risk factors and moving resources upstream to address the stressors that families face and with an emphasis on prevention.

The Indiana Department of Health (IDOH) is one of five sites nationwide participating in a Department of Justice demonstration initiative known as Child Safety Forward. With support from a broad range of technical assistance providers, IDOH has conducted research that identifies unsafe sleep-related deaths as the leading cause of death due to external causes for children ages 0-18 years old, when excluding medically expected fatalities.

Their findings, which focused on Clark, Grant, Delaware, and Madison Counties, highlighted the fact that infants are at a heightened risk for sleep-related deaths and that those deaths were being underreported throughout the state based on inconsistent and incomplete child fatality reviews. Furthermore, they found that inconsistent and incomplete documentation of Sudden Unexpected Infant Deaths (SUIDs) had the potential to limit knowledge of the true rates of SUIDs and the risk factors. High quality, accurate fatality data enables jurisdictions to better understand and address risk factors, promoting the effectiveness and actionability of recommendations.

It is important to note that, in 107 of 140 of the cases identified, children were unknown to Child Protective Services (CPS) before the fatality, pointing to the fact that CPS alone cannot address these deaths and supporting the need for a public health approach to child maltreatment-related fatalities.

Based on these findings, IDOH took several important steps. They developed Community Action Teams in each of the four counties to create avenues for distribution of safe sleep information and resources through pediatricians, vaccination sites, and other channels. They connected with Family Resource Centers and Prevent Child Abuse chapters to share information and identify resources for families.

They also shared their data with government leaders and policymakers, which helped lead to improved SUID policies in Governor Holcomb’s 2022 Next Level Agenda. On July 1, 2022, House Enrolled Act 1169 went into effect, establishing consistent standards for investigations into SUIDs, aligning with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention best practices. This alignment will ensure that coroner investigations into deaths among healthy children who die suddenly and unexpectedly are handled consistently across the state and include imaging, pathology, and toxicology.

Child abuse and neglect fatalities, including unsafe sleep deaths, are not inevitable. They are preventable, solvable and an issue that we all have a stake in addressing. For more information on safe sleep guidelines, visit the Indiana Department of Child Services website on Safe Sleep.

A version of this article previously appeared in the Indiana Herald Bulletin on September 15, 2022.

Disclaimer: This product was supported by cooperative agreement number 2019-V3-GX-K005 Reducing Child Fatalities and Recurring Injuries Caused by Crime Victimization, awarded by the Office for Victims of Crime, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice. The opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this product are those of the contributors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

If there is to be significant change, there needs to be significant research.

In 2020, the Annie E. Casey Foundation, Casey Family Programs, and the William T. Grant Foundation came together to address the gaps they saw in child welfare research. With their overarching goal to reduce inequality within the system, they identified research gaps that spanned community-based family supports, child protective services, out-of-home care, and post-permanency services. They partnered with 50 individuals representing an array of experts, stakeholders, and people with lived experience to identify these gaps. With information from those conversations, they outlined the most urgent needs in the report, Building a 21st-Century Research Agenda. This initiative continues to conduct research to address these identified gaps and answer key questions, as well as increase the use of this research in decision-making.

In partnership with these three leading organizations, Social Current is hosting a five-part webinar series that digs into the research agenda. These sessions highlight different areas of focus within the agenda.

- Cutting through the Chaos by Reframing Childhood Adversity | Oct. 11

- How Monthly Cash Gifts Are Fostering Infant Brain Development | Oct. 13

- Supporting Safe and Effective Investigations through Training Labs | Nov. 29

- Building Protective Factors through Family Resource Centers | Dec. 1

- An Anti-Racist Approach to Child Neglect Investigations | Dec. 6

Together, we can move toward a child welfare system that prioritizes equity and dignity and drives change with greater power and pace.

Read this recent blog by the William T. Grant Foundation to learn more about the initiative.

Hear more from initiative participants in this video.

December 6, 2022 @ 3:00 pm – 4:00 pm EST

This webinar will provide an historical and contemporary overview of child neglect and its link to structural racism in child welfare. Then, the presenter will engage the audience in variations of child neglect definitions and the nuanced interpretations in child neglect investigations. The presentation will conclude with strategies to address and combat racial bias in child neglect reporting and in the substantiation of these investigations.

The 21st-century research agenda for child welfare calls for addressing research gaps in the quality of child protective services (CPS) investigations. Specifically, we need to understand more about how child welfare is responding to allegations of neglect and how improvements can be made.

About the Webinar Series

This webinar is one session in Social Current’s five-part learning series on the 21st-century research agenda for child welfare.

- Cutting through the Chaos by Reframing Childhood Adversity

Oct. 11 from Noon-1 p.m. ET - How Monthly Cash Gifts Are Fostering Infant Brain Development

Oct. 13 from 2-3 p.m. ET - Supporting Safe and Effective Investigations through Training Labs

Nov. 29 from 3-4:30 p.m. ET - Building Protective Factors through Family Resource Centers

Dec. 1 from 3-4:30 p.m. ET - An Anti-Racist Approach to Child Neglect Investigations

Dec. 6 from 3-4 p.m. ET

The Annie E. Casey Foundation, Casey Family Programs and the William T. Grant Foundation are leading an initiative, along with many partners, to identify research gaps related to community-based family support, child protective services, out-of-home care, and post-permanency services. The initiative is now working to conduct research, rooted in equity and co-designed by people with lived experience, to address these gaps and answer key questions, as well as increase the use of this research in decision making. Learn more about the 21st-century research agenda for child welfare online.

Takeaways

- Historical overview of child neglect, poverty, and structural racism in child welfare

- Variations of child neglect definitions in child welfare

- How to address racial disparities in child welfare investigative policies/practices

- Mandated reporting requirements

- Recommendations/strategies to combat race bias in child neglect investigations

Who Should Participate

- Social workers

- Child welfare professionals

- Law enforcement

- Child welfare academic scholars

- Individuals with lived experiences in child welfare system involvement

Presenter

Sherri Y. Simmons-Horton, Ph.D., LMSW

Assistant Professor

University of New Hampshire, Department of Social Work

Related Events

November 29, 2022 @ 3:00 pm – 4:30 pm EST

Child protective services (CPS) can become more effective by investing in a safety culture, where mistakes made by child welfare workers are seen as opportunities to learn and improve. This webinar will discuss efforts to advance safety culture in child protection, including the University of Illinois Springfield’s simulation lab for training investigators. The two training labs, including a mock courtroom, are designed to offer a supportive and safe environment for training students, investigators, law enforcement, and other first responders to identify and respond in cases of child maltreatment.

Webinar participants also will learn about Cook County’s Project CHILD, national demonstration initiative to reduce child abuse and neglect fatalities and injuries through a collaborative, community-based approach. It is funded by the Department of Justice, with technical assistance led by Social Current. In addition, a professional with lived experience will address the importance of well-trained CPS staff.

Effective CPS investigations and contact with families is a component of the 21st-century research agenda for child welfare. It also focuses on equity and the value of lived experience in informing and interpreting research findings.

About the Webinar Series

This webinar is one session in Social Current’s five-part learning series on the 21st-century research agenda for child welfare.

- Cutting through the Chaos by Reframing Childhood Adversity

Oct. 11 from Noon-1 p.m. ET - How Monthly Cash Gifts Are Fostering Infant Brain Development

Oct. 13 from 2-3 p.m. ET - Supporting Safe and Effective Investigations through Training Labs

Nov. 29 from 3-4:30 p.m. ET - Building Protective Factors through Family Resource Centers

Dec. 1 from 3-4:30 p.m. ET - An Anti-Racist Approach to Child Neglect Investigations

Dec. 6 from 3-4 p.m. ET

The Annie E. Casey Foundation, Casey Family Programs and the William T. Grant Foundation are leading an initiative, along with many partners, to identify research gaps related to community-based family support, child protective services, out-of-home care, and post-permanency services. The initiative is now working to conduct research, rooted in equity and co-designed by people with lived experience, to address these gaps and answer key questions, as well as increase the use of this research in decision making. Learn more about the 21st-century research agenda for child welfare online.

Takeaways

- Gain insight into safety culture in child protection

- Reflect on strategies such as simulation labs to improve investigations

- Learn about what role you can play in carrying out a 21st-century research agenda

Who Should Participate

- Child welfare professionals including caseworkers, investigators, managers, researchers, and other social sector professionals who interact with the child welfare system

Presenter

Michael Cull

Associate Professor of Health Management and Policy

College of Public Health

University of Kentucky

Verleaner R. Lane

Project Director

Project CHILD

Gaelin Elmore

Professional Speaker

Gaelin Speaks

Betsy Goulet

Clinical Assistant Professor

University of Illinois Springfield

Coordinator

UIS Child Advocacy Studies Program (CAST)

Related Events

October 13, 2022 @ 2:00 pm – 3:00 pm EDT

Baby’s First Years is the first causal study to test the connections between poverty reduction and brain development among very young children. During this webinar, participants will hear from two researchers behind the study, Sonya Troller-Renfree and Greg Duncan, about the impact of monthly cash support for low-income mothers on the brain development of their infant children.

Baby’s First Years is a pathbreaking study of the causal impact of monthly, unconditional cash gifts to low-income mothers and their children in the first four years of the child’s life. After one year, infants of mothers in low-income households receiving $333 in monthly cash support were more likely to show faster brain activity, in a pattern associated with learning and development at later ages.

How economic and concrete supports can be used promote child and family well-being and prevent child maltreatment is one component of the 21st-century research agenda for child welfare. Understanding the existing research and research gaps in this area is critical as we design better economic stability programs for families and upstream community-based family supports.

About the Webinar Series

This webinar is one session in Social Current’s five-part learning series on the 21st-century research agenda for child welfare.

- Cutting through the Chaos by Reframing Childhood Adversity

Oct. 11 from Noon-1 p.m. ET - How Monthly Cash Gifts Are Fostering Infant Brain Development

Oct. 13 from 2-3 p.m. ET - Supporting Safe and Effective Investigations through Training Labs

Nov. 29 from 3-4:30 p.m. ET - Building Protective Factors through Family Resource Centers

Dec. 1 from 3-4:30 p.m. ET - An Anti-Racist Approach to Child Neglect Investigations

Dec. 6 from 3-4 p.m. ET

The Annie E. Casey Foundation, Casey Family Programs and the William T. Grant Foundation are leading an initiative, along with many partners, to identify research gaps related to community-based family support, child protective services, out-of-home care, and post-permanency services. The initiative is now working to conduct research, rooted in equity and co-designed by people with lived experience, to address these gaps and answer key questions, as well as increase the use of this research in decision making. Learn more about the 21st-century research agenda for child welfare online.

Takeaways

- Learn about the connections between poverty reduction and brain development among young children

- Reflect on ways that economic and concrete supports can bolster well-being

- Gain insight into the 21st-century research agenda

Who Should Participate

- Child welfare professionals including caseworkers, investigators, managers, researchers, and other social sector professionals who interact with the child welfare system

Presenter

Greg Duncan, Ph. D.

Distinguished Professor of Education

University of California, Irvine

Sonya Troller-Renfree

Assistant Professor

Teachers College, Columbia University

Related Events

October 11, 2022 @ 12:00 pm – 1:00 pm EDT

This is the first in a five-part webinar series on building a 21st-century research agenda for child welfare to support child and family well-being. This agenda points researchers toward questions where evidence is sorely needed to make a difference for children and families. However, for that research to make the biggest impact, it will be critical for researchers to communicate effectively about root causes, equity and dignity, and how environments shape child and family well-being.

The science of framing can help. Join FrameWorks Institute for a tour of empirical insights and practical strategies to cut through the chaos and communicate your findings and lessons learned to drive change with greater power and pace.

About the Webinar Series

This webinar is one session in Social Current’s five-part learning series on the 21st-century research agenda for child welfare.

- Cutting through the Chaos by Reframing Childhood Adversity

Oct. 11 from Noon-1 p.m. ET - How Monthly Cash Gifts Are Fostering Infant Brain Development

Oct. 13 from 2-3 p.m. ET - Supporting Safe and Effective Investigations through Training Labs

Nov. 29 from 3-4:30 p.m. ET - Building Protective Factors through Family Resource Centers

Dec. 1 from 3-4:30 p.m. ET - An Anti-Racist Approach to Child Neglect Investigations

Dec. 6 from 3-4 p.m. ET

The Annie E. Casey Foundation, Casey Family Programs and the William T. Grant Foundation are leading an initiative, along with many partners, to identify research gaps related to community-based family support, child protective services, out-of-home care, and post-permanency services. The initiative is now working to conduct research, rooted in equity and co-designed by people with lived experience, to address these gaps and answer key questions, as well as increase the use of this research in decision making. Learn more about the 21st-century research agenda for child welfare online.

Takeaways

- Gain insight into framing science

- Reflect on strategies that can improve your communication

- Learn about what role you can play in carrying out a 21st-century research agenda

Who Should Participate

- Researchers

- Child welfare managers

- Caseworkers

- Social sector professional who work on behalf of children and families

Presenter

Julie Sweetland, Ph.D.

Senior Advisor

FrameWorks Institute

Related Events

The Adoption and Safe Families Act (ASFA) of 1997 assures the permanency, safety, and well-being for all children and youth in the foster care system. These three tenets serve as the framework upon, which the COA accredited organization, Family Builders works to help find permanent, loving families for children and youth in foster care. Their Youth Acceptance Project (YAP), one impressive program among the many they provide, is designed to help one of the most vulnerable, overrepresented populations in foster care: LGBTQ and gender non-conforming children and youth. YAP provides a continuum of services to support LGBTQ and gender non-conforming youth and their families to ensure stable, permanent placements. Jill Jacobs, their executive director, talked with COA about Family Builder’s experiences with serving LGBTQ and gender expressive youth and how it led to the creation of YAP.

History and need

There are more than 400,000 youth in foster care in the United States, according to Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting Systems. A survey by the Williams Institute found that approximately 1 in 5 foster youth in Los Angeles identify as LGBTQ, twice the estimated percentage of youth not in foster care. Many LGBTQ youth in the child welfare systemare there because of rejection from their biological families as a result of making their sexual orientation, gender identity, or expression (SOGIE) known. This rejection places LGBTQ youth at a greater risk for negative life outcomes, including increased chances of health and mental health challenges, homelessness, lower self-esteem, illegal drug use, HIV and STI’s, depression and suicide.

LGBTQ youth often encounter challenges as they navigate the child welfare system. One challenge often encountered is foster families returning the youth to care after they come out; this leads to negative outcomes such as being less likely to achieve permanency and having multiple placements. Other challenges include being more likely to be sexually abused and more likely to face discrimination, including harassment and violence in group placements.

Research has shown that family acceptance is an important protective factor for the long-term wellbeing of LGBTQ and gender non-conforming children and youth. According to a report in the Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, accepting behavior (supportive responses, positive family interactions, open communication, expressing unconditional love) is positively correlated with a myriad of mental and physical health indicators including increased self-esteem, social support, and general health status, as well as decreased depression, substance abuse, and suicidal ideation and behaviors among LGBTQ youth.

Youth Acceptance Project (YAP)

In 2013, Family Builders launched the YAP, which has since grown to become an effective strategy to break down some of the barriers facing LGBTQ and gender non-conforming youth in the foster care system. The program is designed to keep LGBTQ youth safe in their family homes (family reunification/family preservation) and to advocate for safe and equitable permanency of LGBTQ youth when family reunification is not possible. Jill describes the intervention as “kitchen table social work”, working with parents and caregivers of children either in care or at risk of entering in order to increase acceptance of LGBTQ children among their support systems.

YAP Family Advocates are trained Masters’ level social workers that provide advocacy and therapeutic-style support to youth and their families around issues related to the youth’s SOGIE. Family advocates use a psycho-educational model and a harm-reduction framework to address the misinformation, resistance, fear, and grief that families often struggle with; ultimately moving families to a place of acceptance of their child with an emphasis on individualized, culturally responsive supports for caregivers and important adults. The project recognizes that caregivers often experience complex emotions, but with support and education they can become the affirming advocates that LGBTQ youth need. The model of intervention works by building on little changes that then culminate into bigger changes and acceptance, which creates better outcomes for LGBTQ youth. The result is families that become accepting and affirming of their children. The YAP intervention reduces the time that children spend in foster care and reunites children with their families.

YAP outreach

The work of The YAP is expanding across the country. Family Builders currently provides YAP direct services in two Bay Area counties: Alameda and Santa Clara, but is working on expanding their model. For counties and states outside of the Bay Area that are interested in developing a Youth Acceptance Project, Family Builders provides training and consultation services. Family Builders is currently working with Alleghany County’s Children, Family, and Youth Services and the Division of Cuyahoga County Children and Family Services to develop, integrate, and sustain best practices and programs that improve outcomes for LGBTQ and gender non-conforming children and youth in foster care.

Family Builder’s capacity to expand their program and consult with other agencies is due, in part, to the aid of a Children’s Bureau grant. The grant has allowed for them to develop an intensive program designed to prepare clinicians to deliver culturally-competent, ethical, effective support programs to gender expansive and LGBTQ youth and their families and offer follow-up consultation to help support clinicians and agency team members in implementing the program model. In addition to program implementation, the grant will also provide Family Builders the necessary tools and resources to collect data, ensure fidelity, and create a comprehensive evaluation for the YAP model.

Lessons for the field

Jill encourages practitioners to collect data on who is in their system, identify their specific needs, and use that information to inform the delivery of services. “The data has informed Family Builders that LGBTQ kids are overrepresented in our care so we need to include them in our conversations in order to best serve them.” According to Jill, all agency conversations, from supervisions, to case reviews, and file audits, need to have a SOGIE lens. By having conversations that include a SOGIE lens and using data to inform services, agencies are taking steps to ensure everyone in their care is honored, accepted, and affirmed for who they are. “If you’re not looking for LGBTQ kids in your care, then you’re not seeing them, and if you’re not seeing them, you’re harming them.”

This project is funded by the National Quality Improvement Center on Tailored Services, Placement Stability and Permanency for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Questioning, and Two-Spirit Children and Youth in Foster Care (QIC-LGBTQ2S) at the University of Maryland Baltimore School of Social Work. The QIC-LGBTQ2S is funded by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children, Youth and Families, Children’s Bureau under grant #90CW1145. The contents of this document do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the funders, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Direct services in CA are funded by Alameda County Social Services Agency and the Walter S. Johnson Foundation.

The views, information and opinions expressed herein are those of the author; they do not necessarily reflect those of the Council on Accreditation (COA). COA invites guest authors to contribute to the COA blog due to COA’s confidence in their knowledge on the subject matter and their expertise in their chosen field.

You are probably familiar with the ripple effect. The term refers to a sequence of events that is triggered by a particular incident or occurrence. The most common example is dropping an object into a body of water…let’s say a stone in a lake. Once it falls, the stone causes a series of waves that spreads across the body of water, the waves ever expanding their reach. The metaphor is often used to describe the potential impact that our actions have on others and the world around us. At times, we may not even be aware of the ripples that we set in motion.

There is no better way to describe the current opioid epidemic. Opioid dependence doesn’t just affect the individual user; it touches the lives of those around them, leaving its mark on children, family members, and friends. And it doesn’t end there. The ripples grow and extend to countless sectors.

One system that is feeling the impact of the opioid epidemic is child welfare. Reports from public officials, advocates, and those working in the field echo the same sentiment – the current crisis is overwhelming. As opioid abuse continues to increase nationwide, the demand for foster care placements is also on the rise. This leads us to wonder what is the relationship, and what does it mean for families and future generations of children?

In recognition of National Foster Care Month, this article will shed light on the connection between the opioid epidemic and child welfare and contribute to the ongoing dialogue on how policy and practice can better support those working with families entrenched in this devastating crisis.

The scope of the problem

Opioid use disorders and fatalities continue to rise

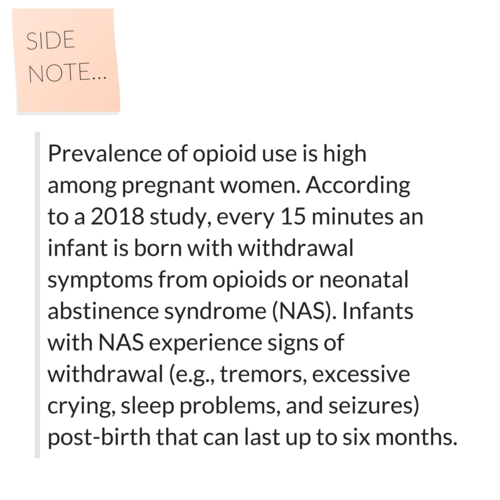

There has been a sharp uptick in the use of opioids since 2010. According to SAMHSA, in 2016, 2.1 million Americans had an opioid use disorder (OUD). As that number continues to rise, so does the number of fatalities. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports that 115 Americans die from an opioid overdose every day.

The number of children who have parents struggling with OUDs is unknown. However, a 2017 analysis yielded that 1 in 8 children resided with at least one parent who had a past year substance use disorder (SUD). The report also found that 1 in 35 children lived in a household with at least one parent who had an illicit drug use disorder. Unfortunately, it leads us to consider that parents are among those that we lose to the opioid crisis on a daily basis.

Foster care placements are increasing

Concurrently, as reports of opioid use rise, the demand for foster care placements across the country has also grown. The number of children entering foster care was on a steady decline for more than a decade; however, the tide shifted in 2012. From fiscal years (FY) 2012-16, the number of children in foster care nationally grew by 10%. While individual states varied, more than two-thirds experienced a surge in foster care caseloads during this period. Six states – Alaska, Georgia, Minnesota, Indiana, Montana and New Hampshire – saw foster care populations rise by more than 50%.

More children are residing with grandparents and relative caregivers

Another recent development is the growing number of grandparents taking on the primary caregiver role. Generations United reports that about 2.6 million children – 3.5% of all children nationwide – are being raised by grandparents or relatives across the country. When we look at the data, 32% of children in foster care are being raised by kin, more than previous years. And that may be just the tip of the iceberg. It is estimated that for every child in foster care with relative caregivers, there are 20 children being cared for by grandparents or other family members outside of the foster care system.

Parental substance abuse is a contributing factor for out-of-home placements

What contributes to the need for out-of-home placements? According to the latest national data, parental drug abuse is a factor in roughly one-third of all child removals. While the proportion of children entering foster care due to these circumstances appears to have remained steady over the past few years, it is increasing. Looking across the different categories for removal, drug abuse by a parent had the biggest percentage point growth between FY 2015 (32%) and FY 2016 (34%), which is notable in the face of the current epidemic.

Connecting the dots

So…is there a relationship between the opioid epidemic and child welfare, and if so, what is it? It’s complicated.

Given the timing of these trends, it is hard to imagine that increased opioid use doesn’t play some role in rising foster care caseloads. A recent national study found that counties with higher substance use indicators (drug overdose deaths and drug-related hospitalizations) have higher rates of foster care entry, indicating a relationship between child welfare caseloads and substance use prevalence. However, we have to remember that correlation does not automatically equal causation (proof that what you learn in statistics will come back around) since we can’t control for all demographic and socioeconomic factors and their potential influence on out-of-home placements.

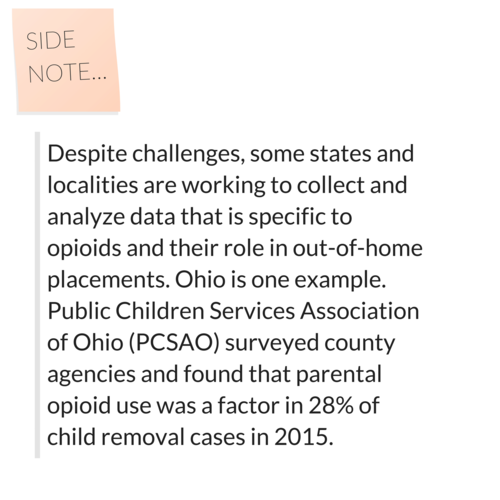

Even though the increase in foster care and relative care placements has been attributed to the opioid epidemic, empirical evidence to prove cause and effect is lacking. This is in part due to the way that the federal government and states track data on child removals, more specifically the contributing factors. For example, there is national-level data on the number of children being removed due in part to parental drug abuse, but it isn’t broken down in a way that shows what type of drug was being abused. Therefore, there is no way to know how many foster care placements stemmed from opioid abuse versus the abuse of another type of illicit drug.

Nonetheless, public officials, advocates and others working in the field are making a direct link between the opioid crisis and increased demand for out-of-home placements. Anecdotally, there are similar accounts across states of the opioid epidemic and its impact on communities. Child welfare agencies are seeing more children come into care because of parental opioid abuse, and children entering the foster care system are getting younger and younger. It has been reported that there aren’t enough foster homes to meet the growing need. Caseworkers are feeling overwhelmed by growing, multifaceted caseloads.

What does this all mean for children and families?

Substance use disorders impact on families

Let’s take a step back. To understand the ripple effect of the opioid epidemic, we have to first look at how parental substance abuse impacts child and family outcomes. At a foundational level, parents struggling with a SUD may not be able to provide for a child’s basic needs (e.g., appropriate supervision or nutrition). Equally troubling, a child can be deprived of emotional support and positive attachment, critical factors in healthy childhood development. Inconsistent parenting inevitability hinders stability in the home. For a child, life can become chaotic and unpredictable, both of which are associated with negative outcomes. That is why parental substance abuse is a known risk factor for child welfare involvement. A 2016 study found that when compared with their peers, children whose parents faced SUD-related issues were three times more likely to experience abuse (physically, sexually, or emotionally) and four times more likely to experience neglect.

Parental substance abuse and child trauma

We know that trauma experienced early in life can adversely impact a child’s development and have long-term health consequences, and parental substance abuse is a one form of childhood trauma (aka an adverse childhood experience or ACE). Often, substance abuse is compounded with other types of adversity, making the severity of potential negative outcomes even worse.

Research shows that history has a way of repeating itself. Children who grow up with complex trauma are more likely to struggle with substance-related issues. One study found that individuals with five or more ACEs were seven to ten times more likely to have issues with illicit drug use. Other explorations into the topic have yielded similar results. There are a host of reasons why people with past trauma experience are more vulnerable to developing a dependence on substance use. While not all children will experience such consequences, the risks to future generations are far too great and warrant immediate intervention. In order to break the cycle, we have to find a way to address the opioid epidemic that is trauma-responsive.

The role of child welfare

The child welfare system is poised to be a catalyst for change. Agencies are tasked with protecting children from maltreatment, abuse, and neglect, and in-home services play a critical role. In-home services are aimed at promoting the well-being of children by ensuring safety, achieving permanency, and strengthening families. When faced with familial challenges, keeping children with their parents is optimal (as long as it is safe and appropriate). Children do best in families with the support of at least one caring adult. Even in crisis, children can thrive when the right protective factors are in place. Removing a child from his or her home disrupts daily life and expectations. All of that instability can be traumatic. The stress that stems from coping with parental loss can have long-lasting effects on a child’s emotional, behavioral, and academic outcomes.

Parental substance abuse has long been an issue for child welfare agencies, one that is now amplified by the recent opioid epidemic. Child welfare agencies across the country are inundated with high caseloads. The complexity of the cases given the unique circumstances and service needs of families battling opioid dependence are adding another layer to an already challenging situation. Not to mention, family stabilization and/or reunification is complicated (contender for understatement of the year). Despite what we know about keeping families together, having children remain with their parents may not be in their best interest due to the impact that substance abuse can have on parenting, making out-of-home placements the safest option. What’s more, reuniting children with their parents can be tricky given ebbs and flows of recovery. The tug-of-war that this creates for caseworkers can be challenging to navigate. So, how do we support those working with families experiencing the crisis firsthand?

Where do we go from here?

Implement what works for families

States and localities are getting creative and implementing interventions that have proven effective for families, recognizing the trauma associated with parental substance abuse. There is ample support for family-centered treatment for substance abuse, including opioid dependence. Additionally, program models that focus on systematic change and cross-system collaboration have also been linked with favorable outcomes.

- Sobriety Treatment and Recovery Teams (START) is an intensive, integrated program for families experiencing co-occurring substance use and child maltreatment. START launched in Cleveland, Ohio in 1997 and extended to Kentucky roughly a decade later. The program matches up specially trained child protective services workers with family mentors (peer support specialists in recovery), behavioral health treatment providers, and the courts. The goals of the program are to ensure child safety and reduce the need for out-of-home care. A 2012 study on the impact of START on family outcomes found that mothers who participated achieved sobriety at a higher rate than those in more traditional treatment programs. Children were also placed in the custody of the state at half the anticipated rate.

- Medication-assisted Treatment (MAT) – an approach that combines medication with counseling and behavioral therapies – is a best practice, and has been linked to decreases in negative outcomes (e.g., opioid use, opioid-related overdose deaths, criminal activity, and infectious disease transmission) and increases in social functioning and retention in treatment, two factors that play heavily into improved parenting skills. MAT has also been found to be effective in providing care for pregnant women who struggle with opioid dependence. Despite some misconceptions in field out the approach, MAT has been associated with improved prenatal care, reduced illicit drug use, and better neonatal outcomes.

- Family Treatment Drug Courts (FTDCs) are specialized courts that respond to cases of abuse and neglect involving caregiver substance misuse. Using a family-friendly approach, FTDCs combine judicial oversight and comprehensive services by bridging together substance use treatment, child welfare services, community supports, and the court system. The unique model balances the rights of both children and parents and aims to create safe family environments while treating the parents’ underlying substance use disorder. In 2015, there were a reported 300 FTDCs across the country, with models and implementation varying state-to-state. The benefits associated with FTDCs include higher participation rates and longer stays in treatment (when compared with non-FTDC participants). The model also yields positive child outcomes; children reportable spend less time in out of home care and are more likely to be reunified with their parent(s).

Support for child welfare agencies and caseworkers

Child welfare agencies are first responders to families in crisis. Caseworkers can encounter stressful or traumatic experiences working with families opioid dependence, witnessing the aftermath of a parental opioid overdose is just one devastating example. That is why supporting frontline staff is imperative.

Provide Specialized Training

Reports indicate that there can be gaps in knowledge among caseworkers around the needs of families with substance use issues and the treatment of opioid use disorders. Training and support in these areas is critical for those working in the field. Additionally, specialized training around recognizing and responding to trauma and trauma-informed care practices is needed when working with families impacted by opioid abuse, as there can be long-lasting negative effects for children if trauma symptoms go undetected and untreated.

Promote Workforce Well-Being

Organizations should employ strategies to reduce secondary trauma and burnout in order to promote workforce well-being. Approaches to reducing the adverse effects of include:

- helping staff identify and manage the difficulties associated with their respective positions;

- encouraging self-care and well-being through policies and communications with personnel;

- offering positive coping skills and stress management training; and

- providing adequate supervision and staff coverage.

Encourage Systems Coordination

Families with substance use issues frequently face other risk factors. Collaboration with other service providers is crucial in helping link parents and their children to the services that they need. The surge in opioid use has trickled into a number of child and family-serving systems. As such, agencies should take steps whenever possible to develop partnerships in their communities to support the work.

Allocate Federal Resources

The crisis is too far-reaching to not have a comprehensive, coordinated federal plan of action in place. Despite declaring a public health emergency, we have yet to devote the level of funds that are needed address opioid dependence. While social service providers and child welfare agencies continue to try and mitigate the impact on a local or state level, the importance of allocating appropriate federal resources to support these efforts cannot be overlooked.

For example, the Maternal, Infant and Early Childhood Home Visiting Program (MIECHV) funds home visiting programs that aim to promote positive parenting practices and healthy parent-child interactions. These programs can also link parents struggling with substance dependence to appropriate treatment providers. Research shows that no matter what level of care is needed, the most beneficial approach is the one that treats families together. MIECHV could help address the unique service needs of the growing number families impacted by opioid dependence.

The Family First Prevention Services Act (FFPSA) may also be a way for federal resources to help child welfare agencies respond to the epidemic. FFPSA is poised to dramatically overhaul the child welfare system, putting federal dollars toward prevention programs and interventions aimed at keeping families together. Substance use treatment programs are among the services that can be prioritized through the restructuring of funds. Additionally, given the increased demand for foster care and relative caregiver placements, advocates are calling to strengthen foster parent recruitment and retention efforts and kinship navigator programs. Increasing capacity in these areas will in turn aid child welfare agencies in finding safe, appropriate placements for children impacted by the current crisis.

There are a variety of other ways that programs and policies could provide relief at a national level; however, equally important is the need for improving data collection across various systems to make informed and evidence-based decisions.

The thing about the ripple effect…

It is hard to stop once it gets put in motion. But that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try. While the current crisis is overwhelming, there are proposed solutions, ones that can positively impact families and change the course for future generations.

We encourage you to share your thoughts on this important issue. How has the opioid epidemic impacted your community and the children and families you serve? What has been the response? Share your feedback in the comments below!

Dr. Robert Block, former president of the American Academy of Pediatrics, has been widely quoted as saying, “Adverse childhood experiences are the single greatest unaddressed public health threat facing our nation today.” That is a statement that many would agree holds true at this very moment, and one that cannot be ignored.

April is child abuse prevention month, and there is no better time to raise awareness around the long-lasting effects of child abuse, neglect, and other types of childhood trauma. This article will explain Adverse Childhood Experiences, share relevant findings from the CDC-Kaiser Permanente Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study, and explore how to put science into practice in order to mitigate the impact of early adversity and toxic stress.

What are Adverse Childhood Experiences?

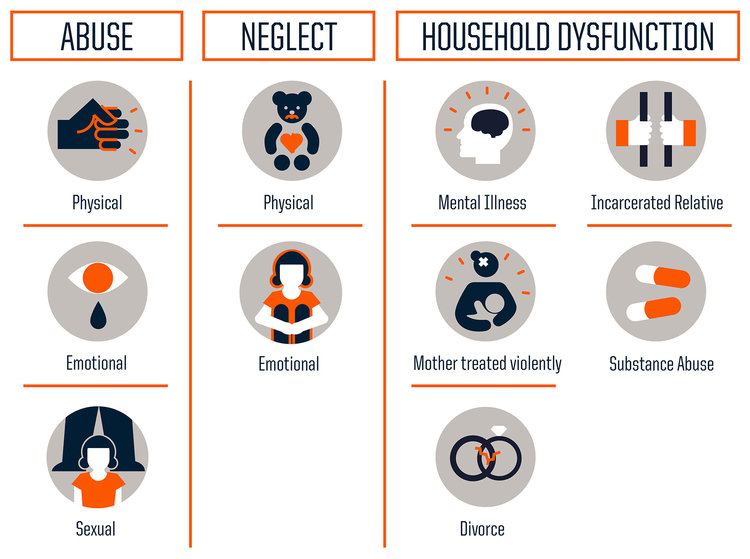

Adverse Childhood Experiences or ACES are traumatic early life events that can lead to negative health outcomes as adults. Much of what we know about ACEs stems from the CDC-Kaiser Permanente Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study, conducted between 1995 and 1997, which examined 10 types of childhood trauma and their impact on long-term health and well-being. Researchers identified three categories of childhood trauma: abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction. The findings were shocking.

The study concluded that the more adversity one experiences earlier in life, the greater the risk of significant physical, emotional, and social consequences in the future. Now, you may be thinking – Why is that so shocking? A difficult upbringing being linked to hardships down the road, what is groundbreaking about that? Well, it is the prevalence at which ACEs occur, and in turn the impact that has on the population. Studies are often criticized for their self-selecting biases, however this investigation challenges that concern. The 17,000+ study participants were predominantly white, middle- and upper-middle class; most were college-educated and had stable jobs and heath care. They represent a group that we don’t typically associate with adversity, showing that trauma has no boundaries and is more common than we think.

Let’s break it down…

Everyone has an ACE score of 0 to 10, with each type of trauma counting as one regardless of the number of times it occurs.

According to the study, nearly two-thirds (64%) of adults have experienced at least one type of childhood adversity. ACEs increase the risk of: chronic disease and health issues, mental illness, engaging in risky behaviors (smoking, substance misuse, and unsafe sexual activity, for example), inadequate social skills, poor academic achievement and/or work performance, and intimate partner violence. The study also showed that ACEs cluster, meaning that if you have one there is a good chance (87%) that you have another. Almost 40% of participants reported two or more ACEs and roughly 12.5% experience 4 or more ACES. The higher your ACE score, the worse the outcomes.

When you look at each type of trauma and look at the prevalence of specific ACEs, the most dominant ACE experienced by participants was physical abuse (28%), followed closely by having a family member with a substance use disorder (27%). However, it is important to note the type of trauma does not impact the outcome per say. To the brain stress is stress; therefore, it doesn’t matter what type of adversity you face, the health consequences will be the same.

When a child experiences trauma, their cognitive functioning and ability to cope with tricky and icky (technical terms) emotions are compromised. Repeated exposure to traumatic events in childhood or prolonged adversity without appropriate adult/caregiver supports negatively affects the way the brain develops and functions; this is known as toxic stress. Toxic stress can be harmful on one’s physical and mental health, yielding undesirable outcomes later in adolescence and adulthood.

Why does this occur? Stressful or traumatic events early in life have a direct impact on a child’s brain development. The brain experiences rapid changes during the first five years, especially from birth to age three. During this informative time, the brain and its neural pathways are susceptible to external factors. While occasional stress is part of a child’s healthy development, chronic stress can negatively affect learning, growth, and behavior. This is in large part due to the overload of stress chemicals and their influence on the brain. When we feel threatened, the body activates our stress response systems and releases stress hormones (e.g., adrenaline and cortisol). Stress reactions and chemicals are meant to protect us, but too much can have the opposite effect. Enter toxic stress. Extended activation of stress response systems in early childhood can disrupt the structure of the brain and the way it communicates with the body, which can lead to major health issues in the future.

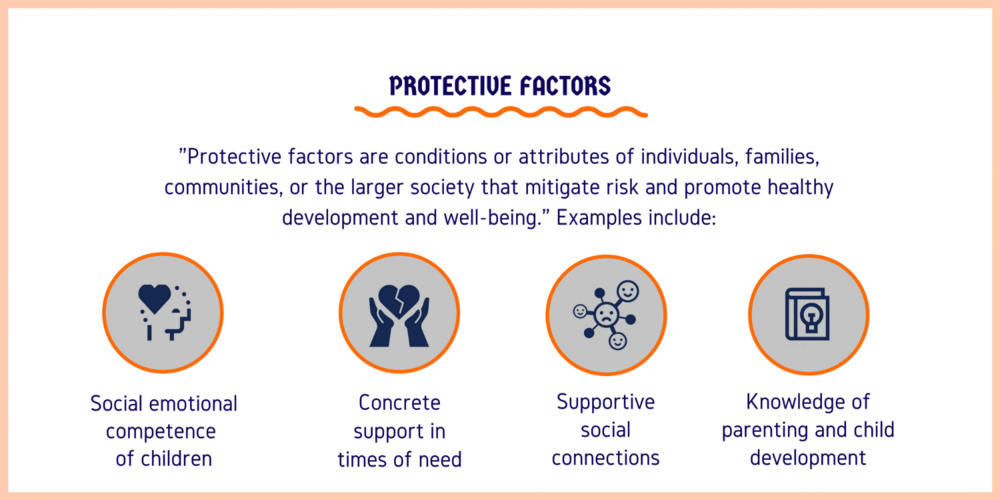

Building resilience

The brain is constantly changing in response to the environment; it is kind of like a chameleon in that way. This adaption is key to facilitating positive change in the face of toxic stress. Creating safe, stable, nurturing relationships and environments are critical to mitigate and prevent the consequences of childhood adversity. While ACEs have the potential to be long-lasting, they don’t have to be; we have the tools to help children thrive in the face of adversity and go on to meet their full potential.

A strong (and continuously growing) literature base has demonstrated that building resilience can help negate stress-induced changes in the brain. Resilience is the “process of adapting well in the face of adversity, trauma, tragedy, threats or significant sources of stress”. Experts in the field of child trauma convey that one of the biggest determinants in being resilient is having nurturing and supportive relationships with adults in one’s family and community. Dr. Bruce D. Perry, a childhood trauma guru, considers “the more healthy relationships a child has, the more likely he will be to recover from trauma and thrive.” And it’s true, adult-child relationships play a significant role in helping children cope with challenges. If stress reactions are time-limited and buffered by protective adult relationships, a child is able to recover and learns how to adapt in difficult situations. That is why high-quality, evidence-based parent education, home visiting programs, and parenting practices are so important. These interventions emphasize the power of familial relationships, caregiver bonding, and positive social interactions. Just as critical are protective factors and their role in strengthening families and preventing trauma. Studies have shown, and continue to investigate, the ways in which different protective factors promote optimal child development. And while intervention can occur at any time – there is no magical cut-off age – there is clear evidence that shows the earlier the better.

There is hope

It’s true that the findings from the ACE Study don’t leave you feeling warm and fuzzy. In fact, at this point, you may be wondering if there is any hope or if we are all doomed. Fear not! This is actually the exciting part (hear me out…).

The ACE Study findings are paving the way for innovative solutions to a public health crisis. It’s cutting across sectors and systems to bridge services and advocacy, and encouraging individuals and groups to collaborate and communicate like never before. From pediatricians to social workers, people in communities nationwide (and internationally) are using ACEs science to join forces and better the lives of children and families. Here are just a few examples:

- The Center for Youth Wellness developed an ACEs screening questionnaire and protocol for pediatric care providers to target more effective early intervention strategies.

- In Manchester, NH, a joint-response team a – Adverse Childhood Experiences Response Team (ACERT) – is bringing together law enforcement, mental health professionals, and community providers to respond to the service needs of children who have been exposed to violence.

- Lincoln High School in Walla Walla, WA incorporates ACEs into their work with students, more specifically their approach to school discipline.

- Trauma-free NYC, a university-community partnership, aims to raise awareness of ACEs and design and promote training and learning opportunities for the larger NYC community.

- Community members and practitioners in Raleigh, NC came together to watch a film about the science of ACEs, Resilience, and have an in-depth discussion around how systems can better address children who have experienced trauma.

A call to action

In her 2014 TED talk on childhood trauma, Dr. Nadine Burke Harris closed in saying, “The single most important thing that we need today is the courage to look this problem in the face and say, this is real and this is all of us. I believe that we are the movement.” Indeed we are. We are the change makers that can combat the effects of childhood adversity. Knowing what we now know, how do we move forward?

Continue to raise awareness

We must continue to raise awareness, not just of the long-term outcomes assocaited with childhood trauma, but also the power of early intervention. Recently, 60 Minutes did a piece on the impact of childhood trauma, highlighting the impactful work of organizations like SaintA and Nia Imani Family, Inc.. The eye-opening conversation was facilitated by Oprah Winfrey…yep, Oprah. The importance of stories like these in mainstream media cannot be understated. We know that when Oprah talks, people listen. Look at the traction that this one segment has gotten over the past month. It’s been invigorating.

Want another example? Sesame Street collaborated with the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation to launch an initiative to help children manage traumatic life experiences. Who better to take on the task than the beloved Sesame Street Muppets? The characters are loved by children and adults alike. An array of research-driven materials have been created through the partnership and are available to children, parents, and professionals. The content is truly original and inspired – it even includes Muppets modeling coping strategies – and emphasizes the power of resilience in the face of adversity.

Now, recognizing that we all don’t have access to Oprah, Big Bird, or a national TV network (wouldn’t that be awesome though?), it is important to take to the platforms we do have at our disposal to spread our message. Post an article on your organization’s Facebook page, email your colleagues, tweet at your community partners…Connecting with diverse audiences ignites new and ongoing conversations around where we are, what we know, and what we can do.

Become trauma-informed

Trauma-informed care is no longer the exception, but instead the expectation. It’s about reframing the conversation from “What’s wrong with you?” to “What happened to you?” There are a great deal of resources out there that provide excellent guidance on becoming trauma-informed, both in clinical practice and at the organizational level. Here are a few that you may want to check out:

- ChildTrauma Academy

- Child Welfare Information Gateway – Trauma-Informed Practice

- National Child Traumatic Stress Network (NCTSN)

- National Center for Trauma-Informed Care and Alternatives to Seclusion and Restraint (NCTIC)

Promote shared learning

Many in the field have been advocating for the implementation of programs and policies that address ACEs, calling for more data and additional research to better target prevention efforts and supports. The fact is that while the ACEs may be new to some, others have been implementing innovative trauma-informed, resilience-building practices in their everyday work to create positive change. We have presented a few examples, but there are many more being spearheaded by individuals, organizations, systems, and communities nationwide. Shared learning is crucial to creating and maintaining a movement.

Be part of the movement

And with that…we want to hear from you. What do you think about the ACE Study and the findings? How are you addressing the needs of children and families who have experienced trauma? Are you implementing innovative trauma-informed practices at your organization?

Share your thoughts in the comments below!